[A BIG THREE-PART NOVEL IN ONE PULSE-POUNDING PACKAGE]

IT… IT’S…

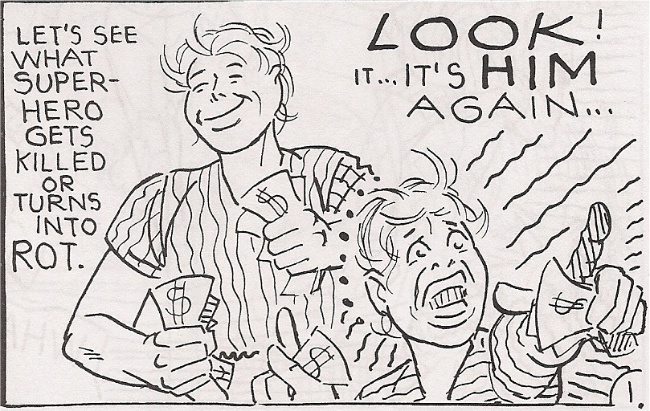

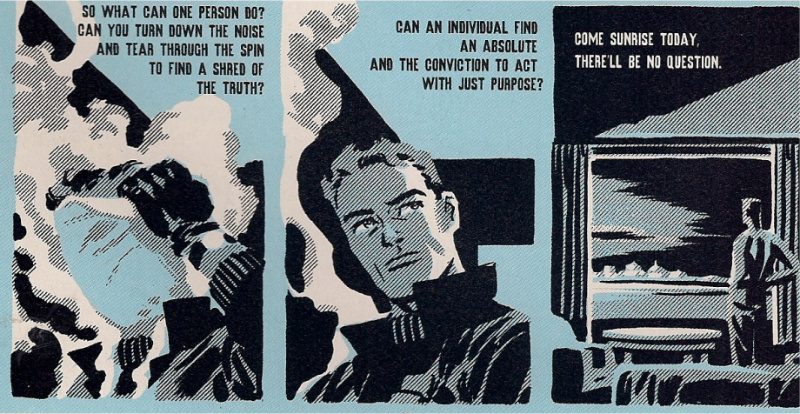

It was a troubling and paranoid time for superheroes in October of 2008.

Secret Invasion was raging at Marvel, a Skrull infiltration so thorough that nary a believer could discern what was true, while DC stood witness to a mass perversion of idealism central to the metaphor of its

Final Crisis. They say that toys are meant to be broken, but even such pragmatic posturing was dispersed as an illusion – Batman died in one issue and came back by the end, because there was so much more to sell.

Just a few months prior to these assuredly reality-quaking events, like a preliminary peal of thunder, Steve Ditko, age 80, a critical contributor to the lucrative spandex sprawl that remains the majority corpus of the Marvel/DC media identity, released a new publication, his first since 2002. It was titled

The Avenging Mind, and prominently featured an essay called

Toyland, initially presented in the pages of

The Comics!, a newsletter facilitated by Robin Snyder, Ditko’s longtime editor, occasional dialogue writer and co-publisher of items since 1988. It was their twentieth year.

Toyland, a reflection upon the ‘breaking’ of superhero ‘toys,’ would briefly become A Thing on the internet in 2009 when artist Batton Lash temporarily posted it, with permission, to the entertainment commentary website Big Hollywood.

By then, Ditko had moved on. While the Invasions and Crises had roared to life in the Direct Market mainstream, the man who once drew several of the crucial participants on both sides — sometimes first — began putting out completely new comic books, starring new superheroes. They were black and white, including the covers, carried no ads, and were not carried by arch-distributor Diamond. An entire wave of them were nearly out by the time online Toy-talk had begun, and plans had presumably been made for a more solidified Steve Ditko: The Series, death of the alternative comic book be damned. It would continue. It

does continue.

For the purposes of this post, I will concentrate on the ten all-new 32-page comic books Ditko has created as of January, 2011. As previously indicated, they can be divided into two ‘waves.’ The first consists of four titles:

Ditko, etc…. (Oct. ’08);

…Ditko Continued… (Jan. ’09);

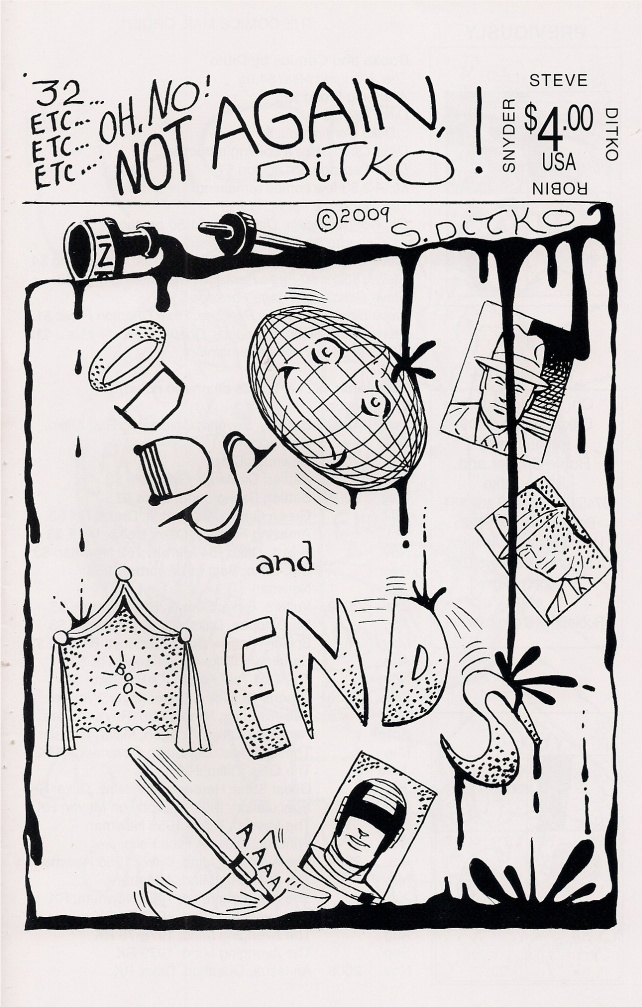

Oh, No! Not Again, Ditko! (Mar. ’09); and

Ditko Once More (May ’09). The second can be differentiated by both a relative emphasis on tightly sequential comics over full-page images, and a unified set of titles:

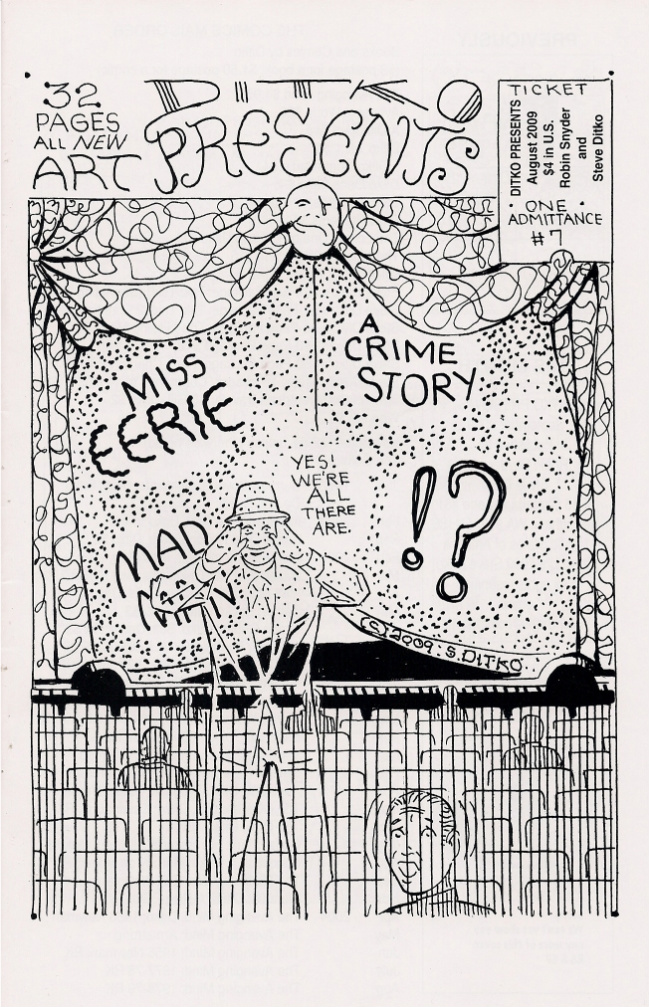

Ditko Presents (Sept. ’09);

A Ditko Act 2 (Mar. ’10);

A Ditko Act 3 (May ’10);

Act 4 (July ’10);

Ditko #5-Five Act (Nov. ’10); and

Act 6 (Jan. ’11).

Structurally, the series lines up with a prior b&w Ditko comic book line, the D series or Ditko Series that began with the 1973 publication of

Mr. A by writer-on-comics Joe Brancatelli — perhaps best remembered for his 1976-80 criticism/commentary column

The Comic Books in the Warren magazines, a well-remembered ’66-’67 Ditko account — who eventually sold off the remains of the print run to vintage comics dealer Bruce Hershenson. In turn, Hershenson published three more Ditko comics:

Avenging World (’73);

..Wha..!? (’75); and a new

Mr. A (’75), at times confusingly designated

Mr. A #4, being fourth in the overall series, although only two of them are issues of

Mr. A. To augment the new line of comics, perhaps in recognition of what’s gone before, Snyder & Ditko have reprinted the ’73

Mr. A and

..Wha..!? in the same format;

Avenging World had already been republished in a massively augmented state in 2002, piling 240 pages of comics and essays spanning over 30 years into a

Cerebus-style phonebook. The aforementioned

The Avenging Mind was its sequel.

I trust you can see the continuity now, and are maybe even anticipating a reprint of the ’75

Mr. A, which would have to come after the imminent

Act 7 Seven (yes, I typed it right), because 320 pages of new work in under three years isn’t enough for Ditko; this level of prolificacy places him at the front of his living peers, among them John Severin and early influence Joe Kubert, although both of those artists frequently work at established comic book publishers such as Dark Horse, Marvel or DC. A more analogous example is Jack T. Chick, longtime independent artist and publisher of evangelical Christian comics, similarly active today in producing new and uncompromising material.

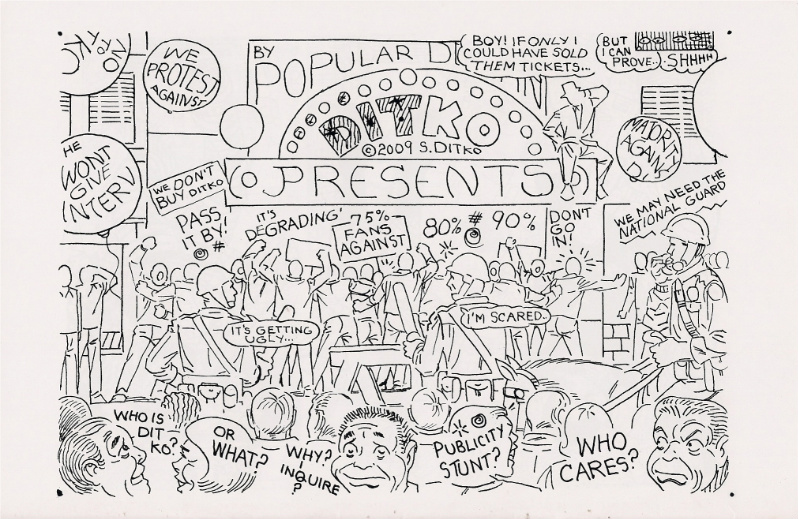

But Ditko does not release his work for free as webcomics, nor do his admirers leave hard copies at cafeterias or bus stops. You can purchase them online, or maybe find a comics store or online service that has somehow obtained them from the publishers. Such distributional circumstances — not unique to any back-of-Previews publisher focusing on bends-when-placed-over-the-edge-of-a-table-style comic books from one artist — coupled with the ferocity of vision evident on any given page of any given issue, has no doubt limited the audience for this new and large body of work from a revered talent, an architect of the contemporary mainstream – a fact that hasn’t escaped Ditko himself. Look again at the cover above, at the audience present for

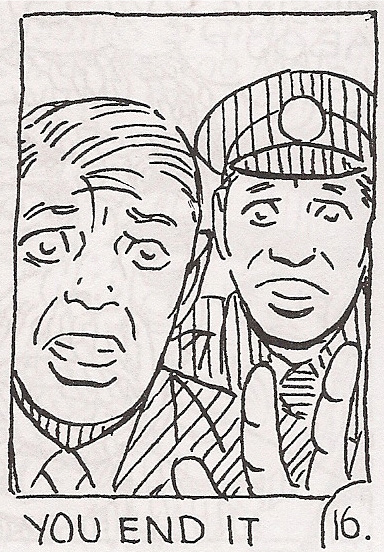

Ditko Presents. I count six people in addition to myself (yourself), in addition to the hovering, cackling outline, about whom more will be said later. “Yes! We’re all there are.”

Here’s the back cover:

This is pretty funny, especially the HE WON’T GIVE INTERV[IEWS] balloon, which can’t be a welcome sentiment at the Alan Moore protest down the street; I think the faceless guys on the center left are trying to find it. Actually, this suggests a small additional joke on Ditko’s part: in that the protest is bordered on both sides by evidently unattached onlookers, the entire demonstration appears to consist of 16 people at maximum, impliedly outnumbered by foregrounded onlookers expressing confusion or disinterest. This seems realistic to me, in terms of Ditko’s standing on the American comics scene —

Oh, is he releasing comics again? Didn’t he go crazy in the ’60s? He drew Spider-Man, right? — and suggests a certain desire on the artist’s part to place the action of his stories in perspective.

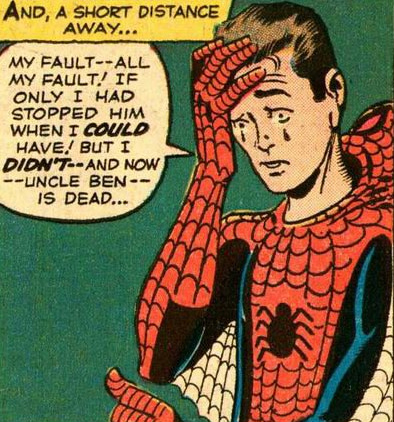

I do think perspective is necessary. Let me show you something.

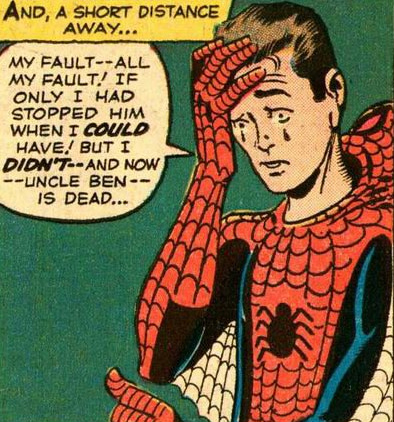

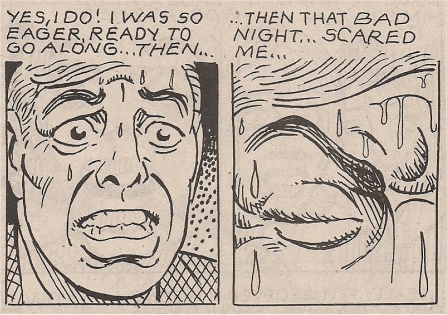

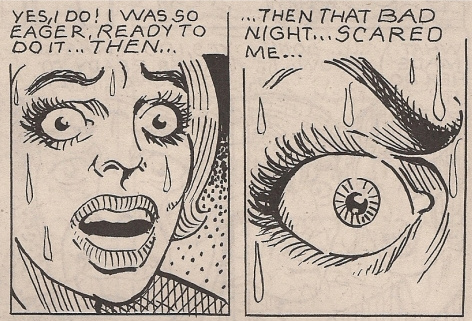

This is so well known, so first-sentence-of-the-obituary recognized — draped so heavily over Ditko’s body of work I can’t help but wonder if the whole ‘theatrical presentation’ angle of the second wave of his new comics isn’t a wry nod toward a certain long-in-production/still-in-previews Broadway extravaganza — it’s easy to forget that what you’re seeing is the teary eruption of conflicting traditions smashing together.

The crux of the Marvel revolution, you’ll recall, was its revitalization of the superhero concept through modification, and occasional generic cross-breeding. Ditko had worked primarily in pre-Comics Code horror comics and post-Code sci-fi and suspense shorts; as luck would have it, Spider-Man was not so much a product of the superhero tradition, as it had developed following WWII into the Silver Age, but a child of

the EC tradition, the cruel twist aesthetic that presided over the pre-Code horror scene and informed much of the trajectory of

Amazing [

Adult]

Fantasy. The ol’ Parker luck, in its earliest incarnation, is distinctly moral, honing in on the objective lapse of Spider-Man’s assent to the burglar’s escape, resulting in the look of agony Ditko so famously captures above.

And it’s not just the look on Parker’s face that will reprise, over and over, hundreds of times on hundreds of Ditko pages, including several of his 320 newest, but

the tenor of the universe itself, soon to be freed from Stan Lee’s diluting perspective, and thereby made hyper-capable of isolating objective instances of Good and Bad, Right and Wrong, and doling out suffering to all those who venture into the black zone from the white, while asserting that no, it’s okay to let the thief go, I’m busy, there’s shades of gray. No no no no no no no. Never mind that Flash Thompson, in some guise, was a bully at Steve Ditko’s high school, or that Aunt May, supposedly, wore her hair like Steve Ditko’s mother – it’s that Spider-Man was born into the Avenging World. The likes of Captain Atom predated him among the artist’s published superhero works, but Parker was fully and firstly

a Ditkovian superhero.

That’s what Ditko continues to create — superheroes, of a rather specific vintage — although there are no scriptwriters to fill in the dialogue anymore, nor is there a Comics Code to restrict the content, nor indeed are there the studio artists and machine lettering utilized by one Jack T. Chick in his never ending battle for you to accept Jesus Christ as your personal Savior.

Here, now, everything is individual.

***

***

(A:

form)

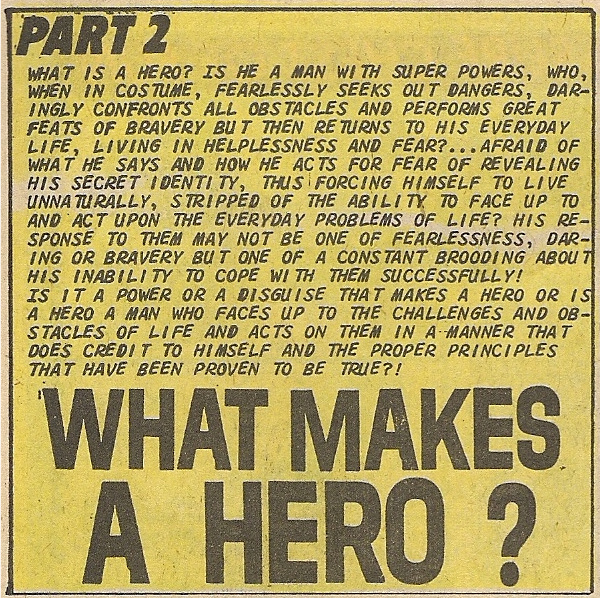

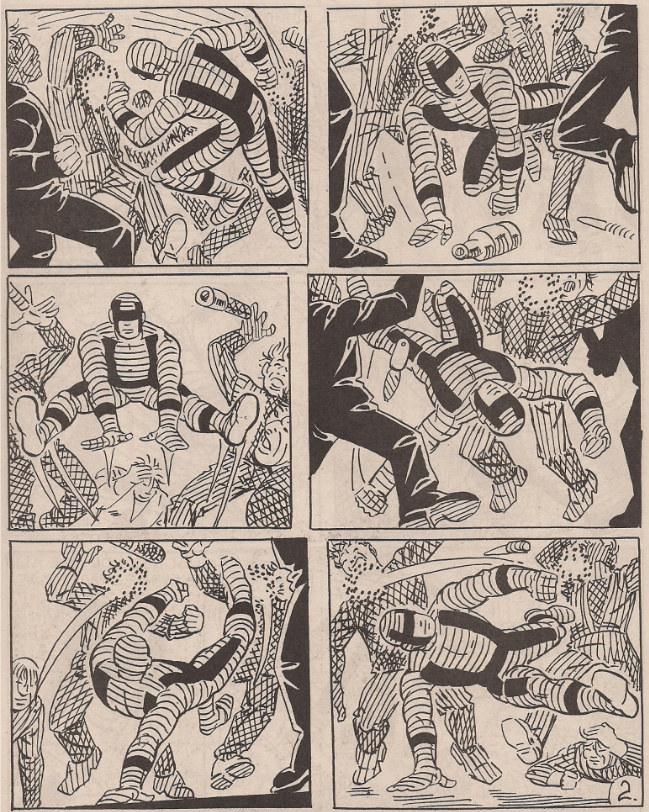

Behold: his natural state! Fittingly, the Hero is the most common character in this new line of Ditko comics – he shows up in all but two of them, three if you count

A Ditko Act II, where he only appears on the back cover, as if patrolling the parameter as chief among concepts. That’s exactly what he is: an honed-down avatar — presented in both the cosmic caped costume as seen above and a more agile body stocking variant for street fighting — for a prolonged demonstration of Ditko distilled.

As you can immediately see, there is little in the way of detail or

abstraction evident on these pages; even compared to the artist’s second-newest body of original work, the 1999-2000

Steve Ditko’s Package line of books, this is honed-down stuff. Some of the Hero’s adventures aren’t even multi-panel comics, but presented as a narrative series of full-page images, showcasing his mighty clashes (or sometimes just pin-up scenes excerpted from multiple clashes) against a series of unsubtly metaphorical threats.

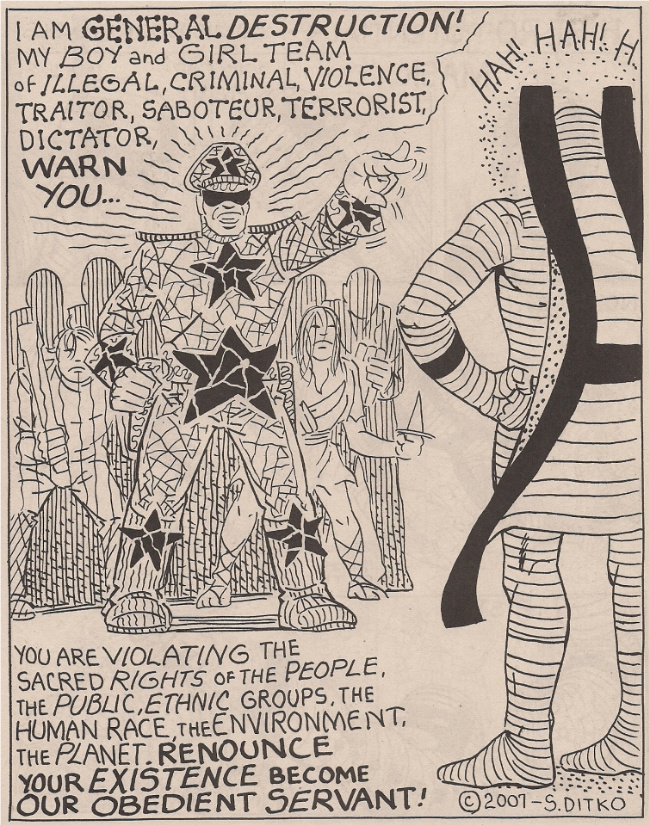

The devout Ditko reader can glean a lot from this image. General Destruction, for instance, is a common-to-Ditko image of Force, which — along with its sibling, Fraud — are what Heroes are bound to challenge in the name of Justice.

Specifically, the military getup is an indictment of the collectivist governmental state, your classic ‘dictator’ image; Ditko is

not attacking the potential collectivism of wearing a uniform in the Army, in that responding force is justified against such an anti-life enormity. Therefore, a standing military is worthwhile as a response to Force in the same way the maintenance of a police force is a rational response to crime, i.e. the Forceful or Fraudulent interruption of one’s individual rights. Indeed — as Ditko notes in his 1969 essay

Violence, the Phoney Issue, revised in 2002 for the

Avenging World expansion — because a dictator rises to power through the initiation of Force, the failure of an outside government to reply with condemnation legitimizes the rule of Force and breeds violence, fear and a hateful view of humankind, especially in the young, hence the Boy and Girl team.

Likewise, the B.G.T.I.C.V.T.S.T.D., while indistinctly drawn — which to my mind makes the guy on the right holding that

huge batch of dynamite all the funnier — are clearly of a hippie/primitive type, generally indicative throughout the Ditko catalog of collective action, violent protest, terror of scientific and technological progress, unthinking opposition to capitalism, mystic beliefs, ecological mania and general mob imbecility. They are just a big, smelly mass of the irrational, in one story (

The Screamer, 1974) explicitly linked to modern cavemen, although they are also a species of the Public, a fundamental Ditko threat usually depicted as a horde of angry citizens jeering and throwing things at a Hero, or even

the Hero. Or a natural opponent:

It does bring to mind a certain batch of protesters outside of a metaphorical theater — comic book fans, the anti-Ditkos — and thereby links right back to the long-haired college kids that served as an early audience for Marvel comics in between rounds of physically blocking the Individual’s rightful access to campus property whilst tacitly supporting the rule of collectivist Force by opposing the conflict in Vietnam.

Now, this is all specialist knowledge, and strictly elective. Part of the beauty of these new comics is how the membrane is stripped from Ditko’s style, so that his work bleeds from ‘story’ comics into a type of editorial cartooning, thereby ensuring that the lines and symbols that fill his pages can signify meaning as efficiently as a donkey or an elephant, forgive my false dichotomy.

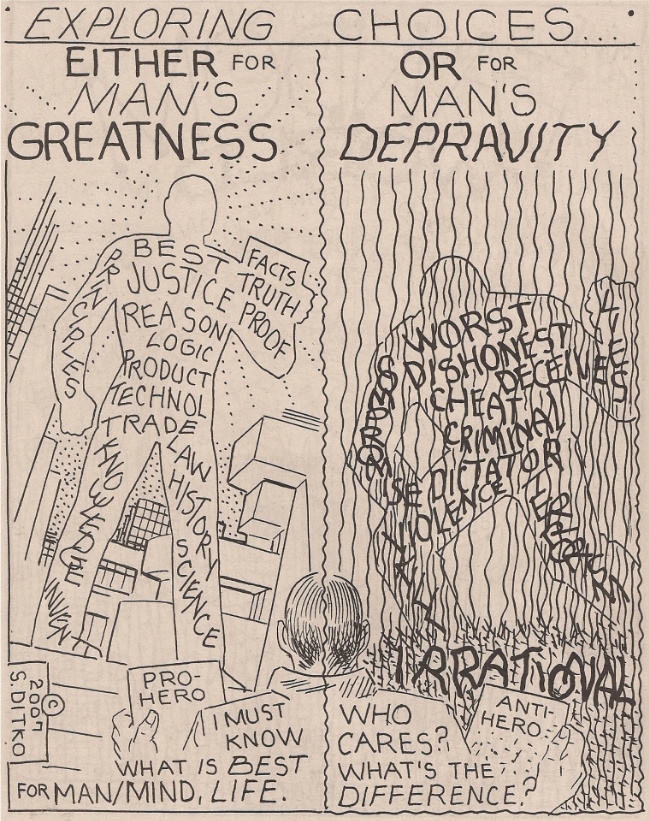

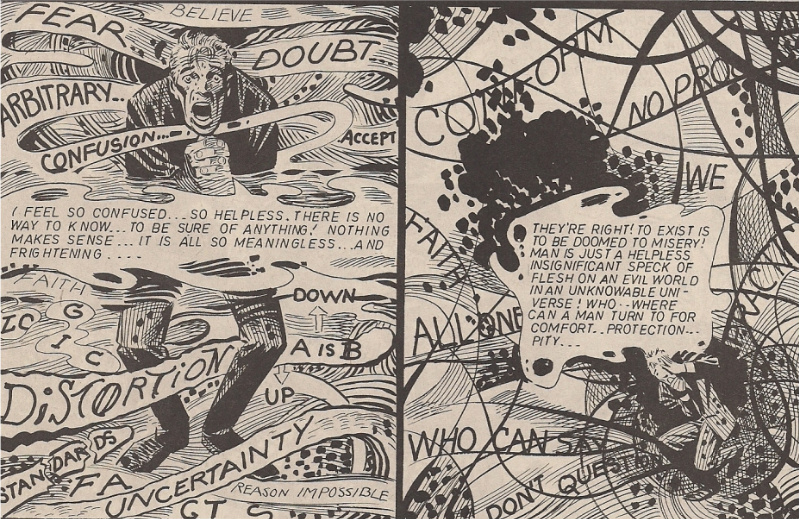

Ah! Not so different from the Hero pages we’ve seen, but this image from

Ditko, etc…. is more in line with the artist’s editorial-type cartooning, a going concern since the late ’60s, and still present to some extent in nearly every issue of the new comics. The most varied example is

Ditko Once More (the last issue of the first wave of the new comics, you’ll remember) which contains eight pages of multi-panel comics, several full-page editorial cartoons/non-sequential poster-like paneled images — often sequenced one after another to chase a common theme — plus an all-splash epic starring the Hero. The comic is

breathing, expanding and contracting through a plethora of states, all formed from the same stuff, and all dedicated to highlighting the Rational basis of Ditko’s universe.

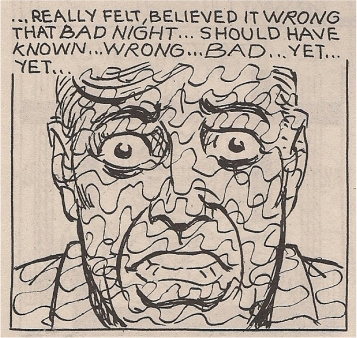

It’s like a code. MAN’S GREATNESS is built from smooth, angular lines, depicting straight towers and an upright human figure. The lettering is tidy, and white space is employed whenever dots radiating from the clear head of the human figure isn’t indicating illumination. MAN’S DEPRAVITY is wobbly all over, with a slinking, muddy form becoming saturated with the unsteady lines that fill the background. Labels are thicker but haphazard, and the only visible environment behind the figure is a thatch of grass that crosses and clashes with all the other lines – in the parlance, it is

undeveloped, untouched by man, and therefore indicative of the absence of progress. Even the central observing figure’s ANTI-HERO paper is filthy, no doubt with bad ideas. Critically, the image’s central line is wavy too, suggesting that adopting a centrist position in this conflict is just as good as plunging headfirst into the muck.

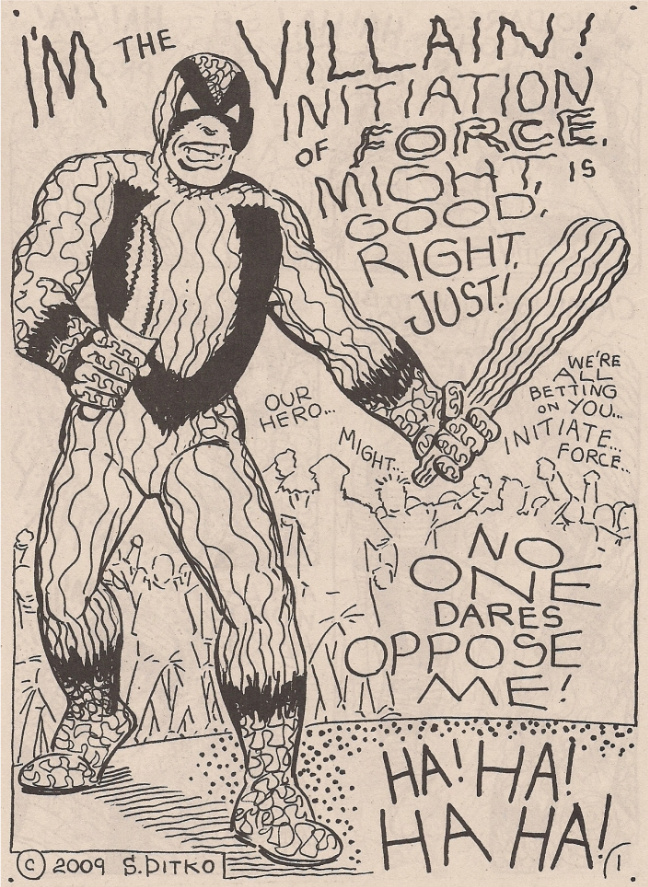

Now compare all of that with the uniform of the Hero. It is entirely composed of clean, neat lines representing zones of black and white, crossing one another in an as orderly manner as Spider-Man’s webs. This design stands apart from the chaos evident on General Destruction’s uniform, the mess of the Villain’s costume flowing from his central collectivist V (two streams meeting at or breaking from a common source), or the absolute bedlam that is the EVIL entity in the uppermost image, tellingly identifying COMPROMISE as among its wicked tendrils. There are no Warren magazine ink washes in this allegorical war of pen strokes; as a result, disorderly patches of crossed lines, squiggles, hatches or whatever-the-hell come to represent the value of ‘gray,’ identical then to white stained by black, which Hero-Philosopher Mr. A reminds us is all gray ever really is: a corruption.

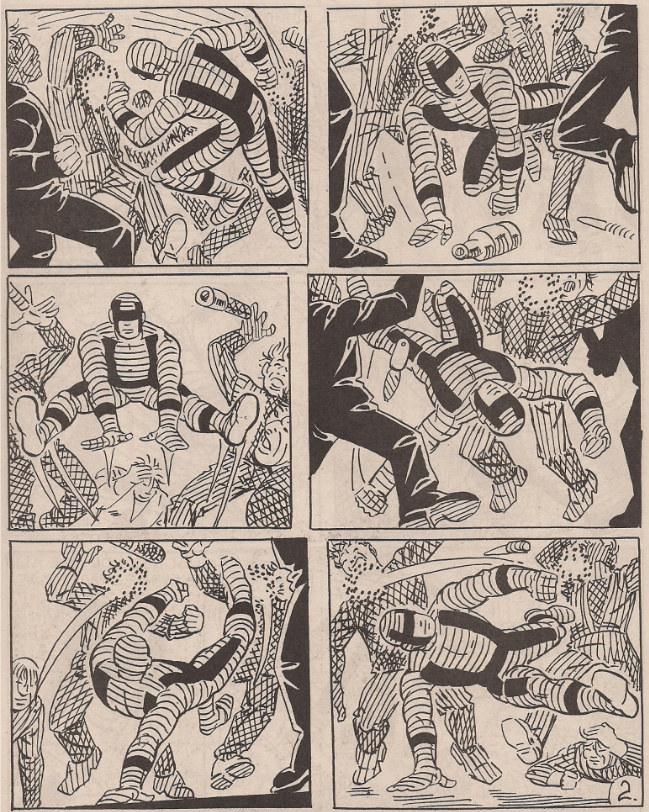

These values are present in sequential images as well – it’s typical for Ditko to contrast a heroic flourish of orderly divisions of black and white from more tangled visual forms. The just nature of the Hero is signified by his steady, separate lines, marked only by tiny folds in which his costume presses against his presumably human skin, doing battle with chaotic human opponents, their bad nature laid bare by their natty attire.

In a way, this display makes for good storytelling: the hero is easily distinguishable from his horde of attackers, with his mighty blows emphasized by zones of white space demarcated by little dot clouds. At the same time, these fundamental storytelling qualities are charged with specific meaning to Ditko, so that the clearer, nary-a-wasted-hatch design of the Hero is emphasized as not just a visual figure but

a philosophical ideal, innately superior to the jangle of opposing forms, which are duly obliterated bit by bit by the illumination of his lined fists connecting with their agonized faces – appropriately, the only uncluttered area on their bodies, so as to better communicate the suffering of the unjust.

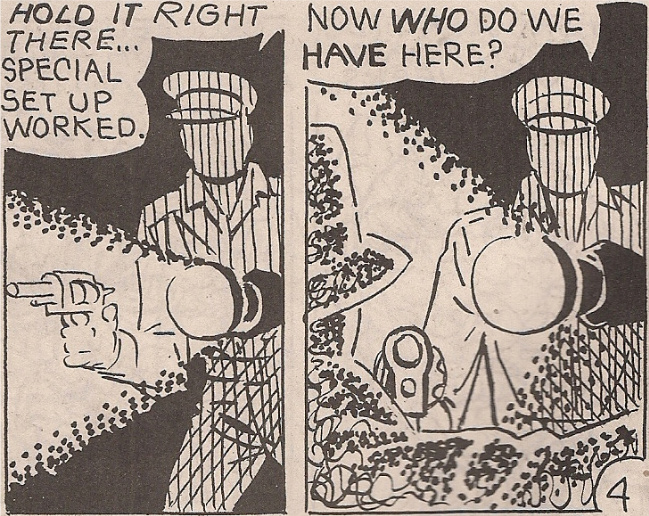

This is a more complicated image, depicting entirely shadowed figures in panels one and two advancing toward an illuminated door, behind which the Hero resides. In panel three, he stands ready and grinning in a white area while a supervillain bursts through to his space and a potential victim, reeling in a dot-clouded shock of realization, lunges into the shadows, invasive lines crossing his body – he is not a bad guy, not immediately, but the measure of his character allows for infestation by the clashing directional lines/shadows/gray-is-black.

Mind you, these visual properties are not hard and fast – Ditko’s style these days is limited enough that these devices must also function in a diegetic manner, indicating the in-panel presence of actual light, shadow, etc., so that a superhero might dramatically emerge from the shadows or, as seen above, a villain might be seen clearly under harsh light. Yet there is almost always some usage of the revelatory iconographic values Ditko attributes to the fundamental elements of his craft — lines, dots,

marks — so that meaning is readily ascertainable apart from the usage of text or the sequential build of meaning across series of panels, or even the positioning of characters in-panel.

Such is the basis of Ditko’s approach to his new comics, although certain aspects are visible in far earlier comics; take this

Blue Beetle confrontation from 1967, in which a beatnik-like collective of villains discovers the none-too-subtly metaphorical and blindingly literal functions of Ted Kord’s gun. Watch for the surrounding dots:

It drives out the shadows, you see. Ditko is less literary now – if his pen strokes are evidence of physical age taking its toll, they have only made him more determined to communicate his message immediately. This is the immense personal beauty of these comics: they are too damn old for gratuitous flourish, and so it is shown that Ditko’s all-encompassing message is present in the very marks that distinguish form from void. The message is atomic. The Hero, so simply named, is the basis from which all variations will derive, the molten center of Ditko’s ideological planet.

And if his adventures never really function as anything other than inevitable victories over barely-defined foes — most of them are

just barely stories at all — we much recognize their central, gravitational position, and know that the the ‘H’ down the tights of the title character is just as good as prison bars holding the howling guilty.

So how about a fuller story?

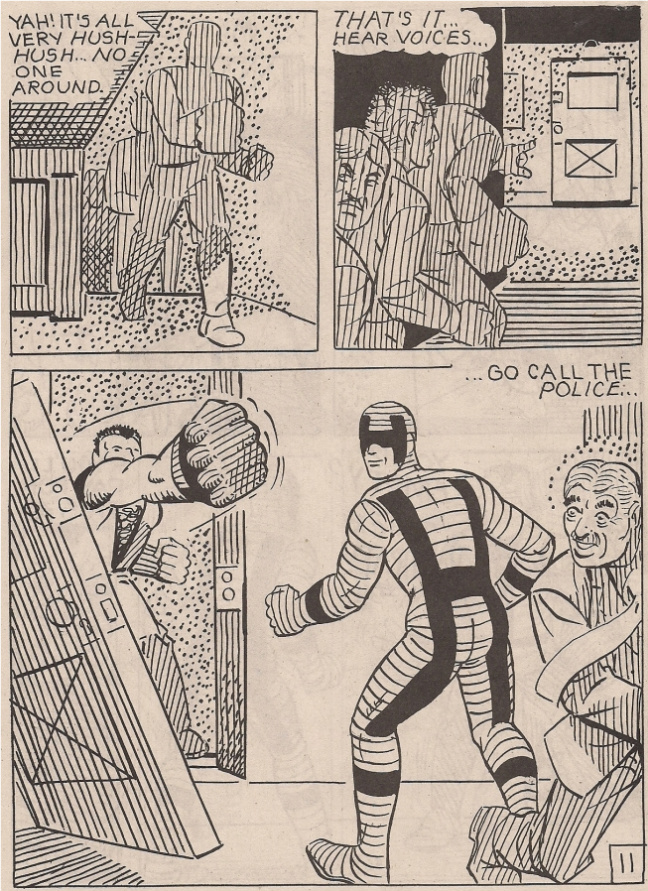

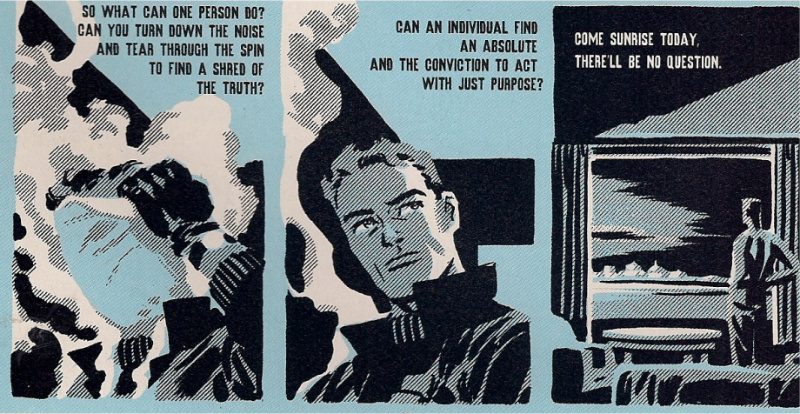

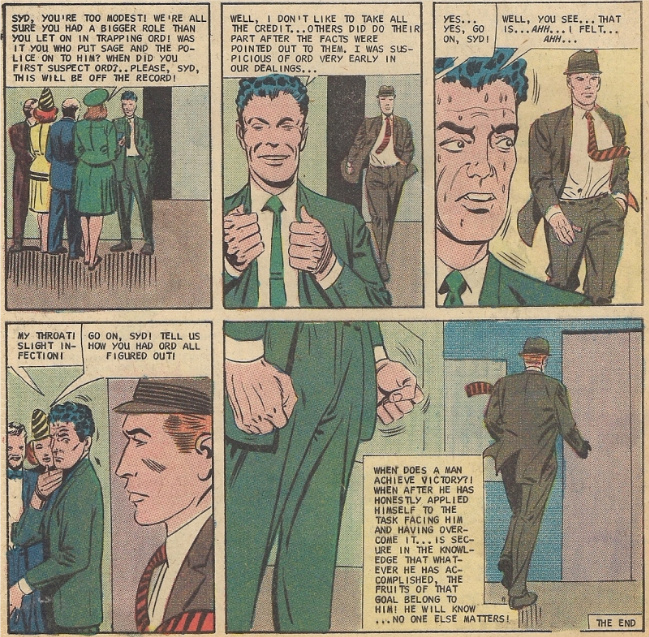

The Wishers is a one-off concept from

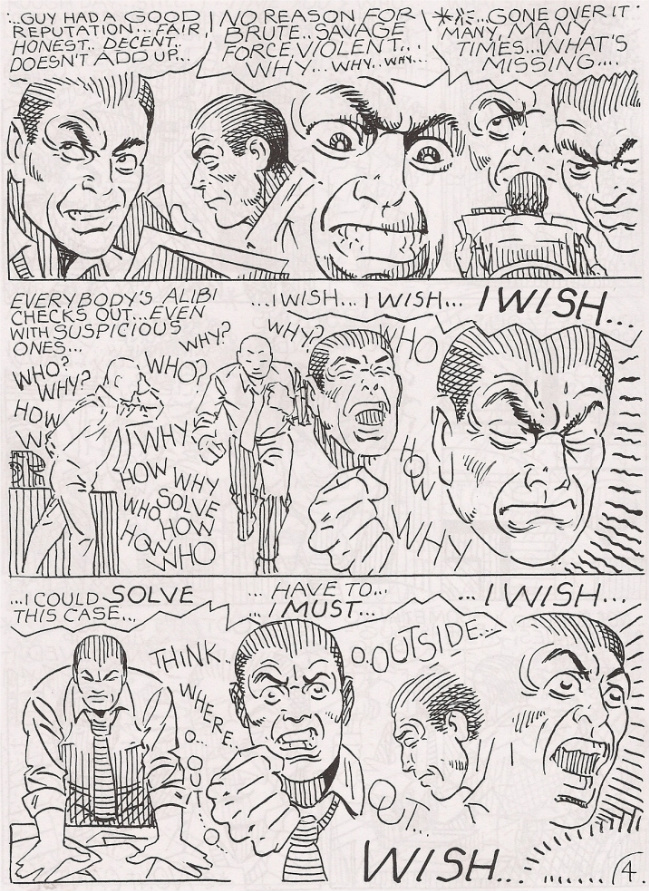

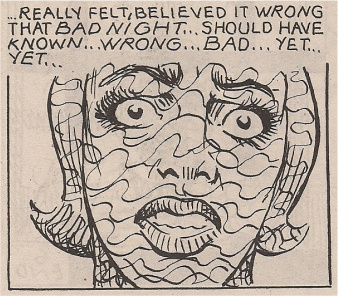

Ditko #5-Five Act, concerning a pair of men engaging in what can only be called Combat Wishing: on page one, the antagonist enjoys a perfect revelation for how to murder his hated supervisor — beating him to death with a club in an alley — only for a driven police detective, the protagonist, to wish his way to the solution, after which the simpering assailant is arrested. Six pages. Immediately, we can see that Ditko’s layout is more complex, with emotive faces and bulging eyes coursing through an atmospheric swamp of lines and illuminating dots – while typically indicative of the illumination of Reason, Ditko knows that such devices are neutrally valued on their own, and rely on some context for assignment of meaning. I’ll get back to that shortly.

Right now, look at the text. If there’s one thing almost everybody will pick up on immediately in these comics — aside from ‘not a lot of spotted blacks, huh?’ — it’s that almost nobody speaks in complete sentences. To some, this can be taken as a departure from the stereotype of Ditko’s characters standing around all the time, possibly crunched down toward the bottom of the panel, coughing out sentence after dense sentence of declarative philosophy. However, the ‘abridged’ technique dates back to at least the early ’70s, running parallel (if not quite at identical length) with Ditko’s textier works. Its primacy here can be taken as an additional honing of the artist’s style, in which the character and positioning of the lettering is granted the same atomic meaning as everything else constructed from Ditko’s lines.

Believe it or not, this reminds me of one of the galumphing superhero Event comics I cited back at the top: the Grant Morrison-written

Final Crisis. It’s a deeply flawed work, redolent with compromises — not the least of which would be a lineup of fill-in artists deployed to keep the machine running in time to set all the other books of line onto proper money-making, crowd-pleasing schedules — which would have sent Ditko running for the parking lot, possibly through a window and down the fire escape. Yet in its massively compressed later issues it touches a sort of manic beauty, vacillating between dull genre punch-outs and fractured panel-by-panel scene shifts, vivid enough that I wondered if Morrison shouldn’t consider a type of superhero Lettrism, breaking dialogue down to the basic elements of visual symbols.

To an extent, this is what Ditko is doing. In a 1990 essay,

Tools of the Trade (rev. 2002 for

Avenging World), Ditko identified the usage of words in comics storytelling as fundamentally abstractions, concepts born from an image-based narrative in the writer’s head. In contrast, pictures are concrete, functioning as perceptual rather than conceptual. It’s an old saw that Ditko can’t write naturalistic dialogue, but to my mind his prolix approach can be

operatic, in that his characters seem to pause, even when demonstratively performing some action, to clear the air as to their innermost feelings. Jack Kirby’s work might

seem like it fits the playbill, what with the clashing gods and thrusting bodies and costumes and etc., but those are surface considerations on top of a fairly traditionally ‘superhero comic book’ brand of storytelling, the kind that bids me to slow down in reading even his most krackling Fourth World chapters; I never have this problem with Ditko, at least when he’s writing the story, because his concern is never so much on characters striking plot points while steadily communicating ‘like people talk,’ but in varying recitative passages with philosophic arias, so as to a give-and-take between the concrete actions of his characters and the concepts they represent.

The Wishers is not, however, so classically an operatic work; perhaps it is Wagner’s

Gesamtkunstwerk: a total work of art. Ditko now uses words as integrated elements of his visual, concrete images, essentially coloring our perception of his lines — as always, charged up with the meanings discussed above — with surrounding, complimentary wisps of concept. Only the dead basic amount of verbiage necessary is used, much in the way Ditko’s art seems to consist of outlines; adventurous characters speak often of “a long shot,” simpering cowards whine about “rights,” and the good detective just above paces and paces so that his words surround him, tiny asterisks and starbursts indicating cusses, which the Individual reader is left to fill in, along with each sentences’ completion.

But what of the total meaning? Go back and look at both pages; they’re not exactly mirrors, but they do serve to depict alternate Bad and Good, Black and White versions of Combat Wishing. Surrounded by mad, scrawled lines, ghostly faces and all manner of visual noise, the killer arrives at his rather stupid plan through irrational, emotional means. The Hero, the police detective, is no less intense, but his space is clearer, filled with concepts,

words, which in a unified display bespeaks his rationality. This, on the page, is why he triumphs.

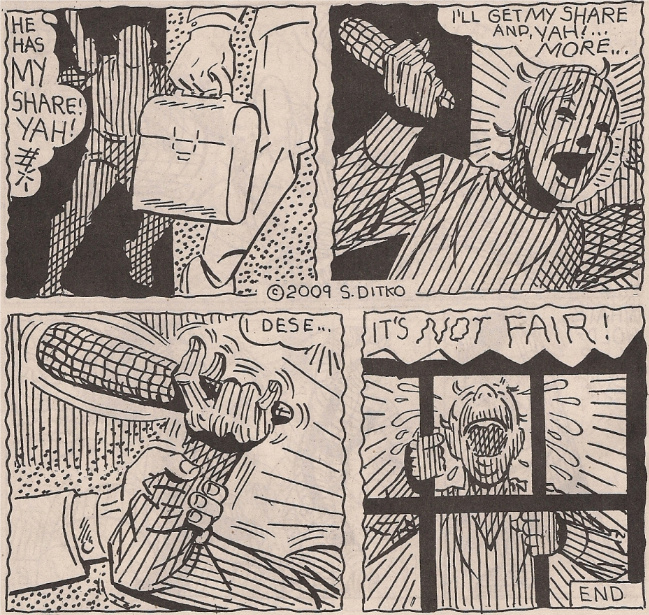

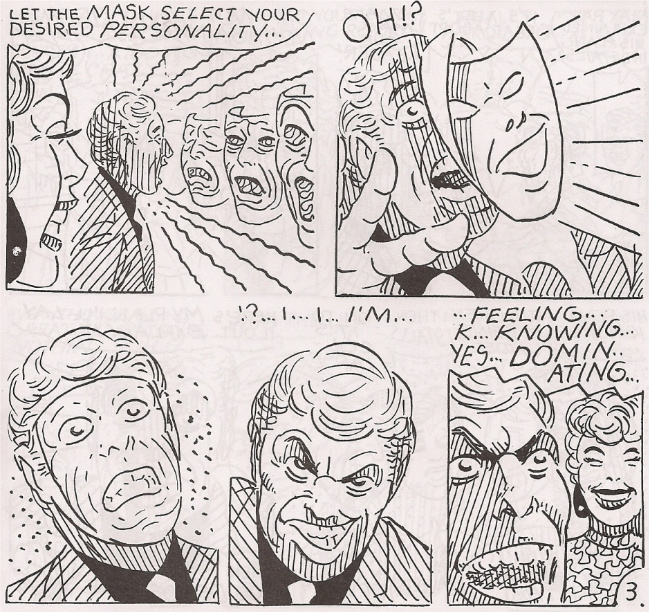

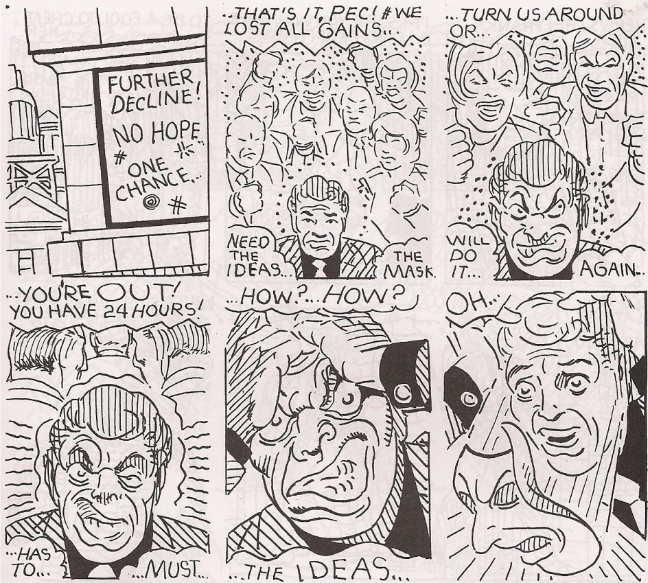

Here’s another one-off piece,

The P Masks, from the newest-of-new

Act 6. Textual clues suggest that the full title should be The Personality Masks, and it says everything about Ditko’s atomic approach that the wearing of a mask is indistinguishable from walking around facially nude. Note how the mask throws off detail as it approaches the buyer’s face, eventually behaving as a sort of clear film that scrunches him up a little until he’s used to it.

The plot, as it is, likewise obliterates the distinction between generic masks; it’s slightly closer to one of Ditko’s myriad Charlton thrillers — the heart of pre-Code horror beating hard in a less favorable climate — than a superhero comic. Nonetheless, it operates on the same basis as all of Ditko’s new comics: a man is agitated that his outdated ideas are unpopular at the office, so he buys a devil-may-care P Mask from a grinning mystery woman’s shadow boutique. He becomes the hit of the company, but hubris demands he refuse to make full payment on the merchandise. Suddenly, his skills become weak.

Rushing back to the store, he fails to see a mistreated underling walking out with his own new mask, vowing not to become greedy or stoop to cheating. Time is up; asking for directions, the maskless man discovers that the boutique’s proprietor has no face at all. He flees, screaming.

It seems almost dreamlike from evaporating the plot content from a bad-man-gets-his supernatural scenario, but it can be understood in much the same way as

The Wishers above; to deprive one of property, including his life, is to assure your downfall via a more Rational being. What Ditko does here is remove the human element altogether and have the Bad character defeated by the very mechanisms of the Avenging World, which assures us that man in fundamentally a Rational being, and that deviations from this state will be dealt with in due time. It also explains why an avowedly anti-supernatural personality such as Ditko would work so much in horror comics – because the mechanisms of some horror comics, the ironic reversals and spectacular feats of vengeance sprung from the dirt of their graves, are metaphors for the half-visible activities of Ditko’s own comics, promising the victory of Good.

It sounds a bit… superheroic.

***

(A:

content)

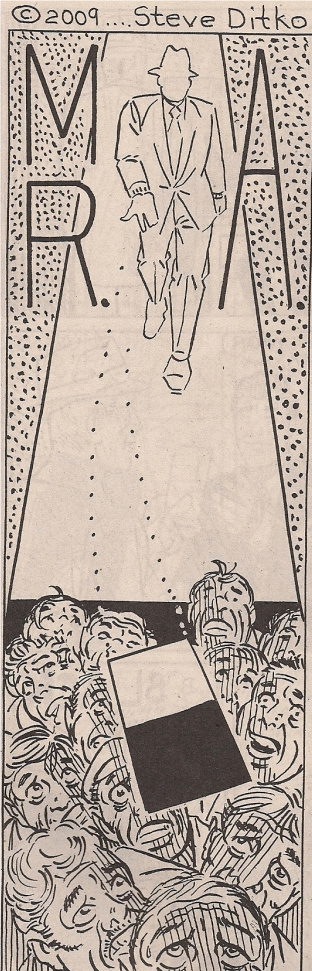

Now here’s a guy everybody’s heard of. Indeed, Mr. A is so well known it’s easy to forget that he sat out the entirety of the blood & thunder anti-hero ’80s and the grit-muscled ’90s; all of his ‘vintage’ appearances were collected by Fantagraphics in its two-volume

The Ditko Collection in 1985 and 1986, after which the character made a comeback appearance in 2000′s

Steve Ditko’s 176-Page Package, directly preceding his newest appearance serialized in

…Ditko Continued… and

Oh No! Not Again, Ditko! It’s a good thing the artist pushed this out before the ‘theatrical’ wave of comics, or he’d probably have had to figure out a way of depicting the five or ten minutes of applause the character would receive upon taking the stage. A = standing O.

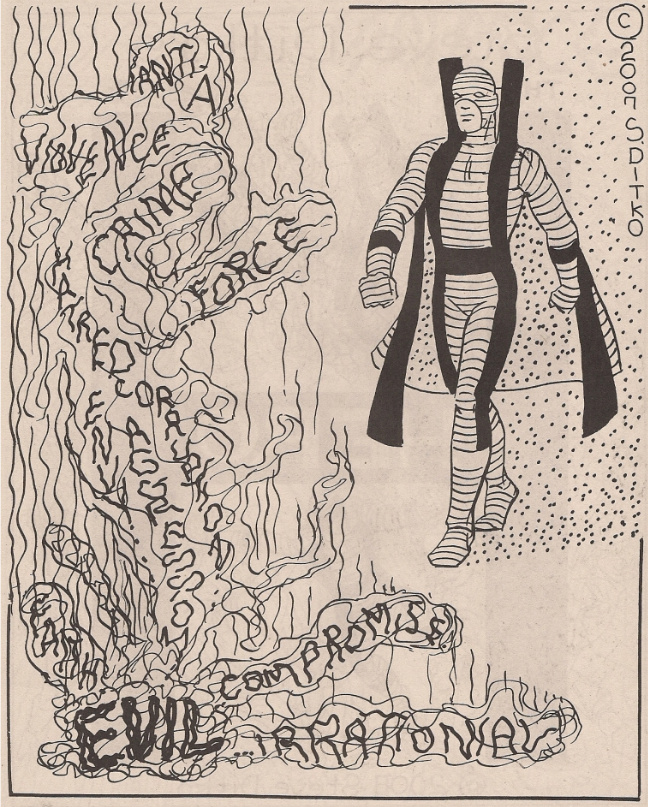

A lot has been said about Mr. A, not just because he’s the most visible of Ditko’s philosophical superhero creations, but because for a while he was the walking, talking, two-fisted summary of the artist’s point of view, now dispersed over hundreds of pages of Ditko comics. If the Hero is the core of Ditko’s newest work, Mr. A is its living history. But there’s more history present than is often explored; what’s typically forgotten about Ditko is that he’s of the first generation of comic book professionals who grew up reading comic books. He loved Will Eisner’s work on the Spirit — which would have launched as a newspaper insert when Ditko was 12 — and specifically sought out Jerry Robinson’s tutelage at the Cartoonists and Illustrators School in NYC because he admired his work on Batman. While many artists entered comics as a means of getting a foothold in illustration or industrial art or newspaper stripping — not unlike how some of today’s graphic novels seem specially presented to attract the eye of movie studios — Ditko by all available accounts went into comics to make comics. To use contemporary superhero terms, he was a fan-turned-pro.

And while thoughts of fans-turned-pro in superhero comics typically raise thoughts of tangled, anal continuity spiraling like rotten DNA unto eternity, Ditko approached the superhero genre as primarily a means of self-expression. Keep in mind, Mr. A debuted

the year after Ditko left

The Amazing Spider-Man, instantly re-mapping the superhero genre as a means of incarnating the ideals cherished by the artist into a wise, brawling avatar of the Avenging World, a metaphoric guarantee that Reason would always triumph over Force and Fraud, clad in film noir threads to turn Denny Colt green. Why noir? Why such a downbeat source? I don’t know – why horror? Why not set the Hero up as a shining beacon in a world that only seems doomed, dominated by high-contrast shadow black against glorious blinding white.

That Mr. A first appeared in issue #3 of

witzend, a Wally Wood-founded independent comics anthology premised on giving working professional cartoonists a forum for personal expression, says less to me than the character’s many additional ’60s and ’70s appearances in fanzines, a means of Ditko-the-fan to interface with an increasingly organized comics fandom in pursuit of the superhero ideal. It would turn antagonistic, of course, but that is an inevitability in the comics too.

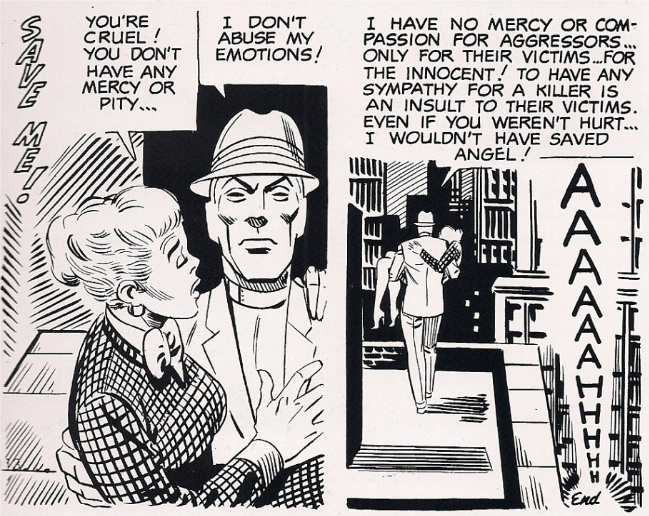

This is from Mr. A’s first adventure, published in 1967. A bleeding heart in his arms, steely reporter Rex Graine strides away from some screaming teenage murderer as he plunges to a deserved death. Mr. A could have saved him, but he didn’t, and if you think that’s a blemish on

his record you’re indulging in compassion for instigators of Force when none is warranted. Crucial to the Mr. A persona is the concept of “retaliatory force,” couched as self-defense by Ditko in

Violence, the Phoney Issue, which was in fact headed by a drawing of Mr. A, a most ‘violent’ hero for the time.

It is not difficult to criticize this content. Mr. A and all of Ditko’s Heroes — some would say all superheroes, fundamentally — are at-heart reactionary, in that they only oppose cognizable, committed criminal acts. Laws only seem to exist at all in Ditko’s comics as either a means of disposing of criminals that aren’t killed or a target for anti-Individual/Identity/Life dismissal. The political process is never acknowledged, although seemingly any organized dissent to the status quo is branded Collectivism and implied to be at-heart Force, inferior to the fact-gathering Reason of the Individual, who presumably has to reach some agreement with other Individuals to function in society, mostly off-panel in Ditko’s comics. It almost goes without saying that the proper function of a newsman like Rex Graine is through unyielding activist journalism, in that ‘neutral’ reportage with the pretense of delivering both sides of an issue regarding Force or Fraud is automatically supportive of Force or Fraud in failing to rebuke it, white corrupted with black, etc.

Not all reactions of the material need be dismissive, however. Above is a piece by Darwyn Cooke, from issue #5 of the 2004-06 DC comics anthology

Solo. Cooke sees Ditko’s the Question — a Mr. A variant Ditko created in the pages of

Blue Beetle, a Charlton superhero series over which he had been given much authority following his departure from Marvel, the ‘Q’ to Mr. A’s answer and a suggestion of proper superhero activity inserted into company-owned genre stuff, the white ‘corrupting’ the black — dash off to the Middle East to solve America’s post 9/11 problems in an exceedingly limited manner, i.e. sneaking in and out to tactically eliminate the specific initiators of Force. In this way, Cooke selectively reads Ditko’s philosophy in tandem with the rules of his comic book storytelling, and arrives as a ‘perfect’ result, perhaps absurd in a world living with an Iraq War — not necessarily a wrongful effort, given the Ditko stance against dictators — but sympathetic to the appeal that being scooped up by a winning superhero and carried off as innocent can have.

Today the Question is a vastly different character — continuity’s price — but he occasionally provides interested artists with a means of ‘doing’ Ditko’s philosophy in the context of a popular superhero book, in that the Question is barely a step away from Mr. A, who is the great icon of the Ditkovian superhero. Frank Miller did it in

Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again, and Grant Morrison will presumably do it in his upcoming

Multiversity, although such an effort will surely be taken as a response to the genre’s big Ditko-influenced work:

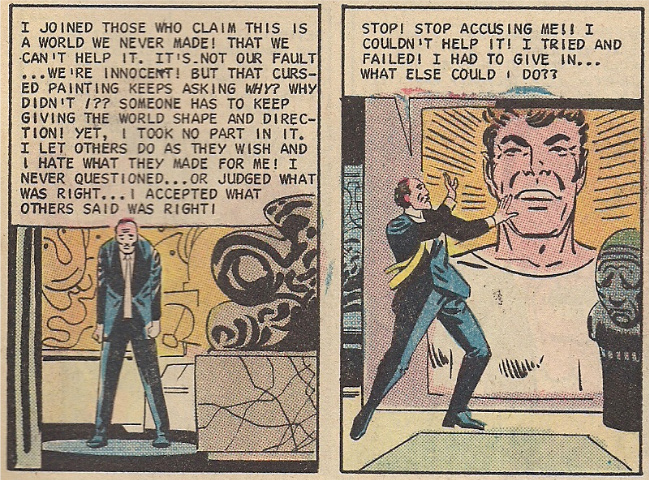

Only through an intense examination of Ditko’s work is it possible to appreciate exactly how thoroughly he was parodied by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons in their seminal

Watchmen, through the Question analogue character of Rorschach. For one thing, Moore takes the clipped manner of Ditko’s ‘abridged’ style of dialogue and hardens it a little into fuller sentences to make it sound like the rantings of a mentally ill person. Instead of proudly embodying the best in humanity as a crusading reporter, Rorschach parades around in his civilian guise declaring the end of the world, eventually submitting his work to a fringe right-wing magazine. His noir uniform is stained and filthy in a mockery of Mr. A’s clean white gear, so essential to embodying the white (good) vs. the black (bad).

Moreover, in visual terms, the name Rorschach signifies a blend of white and black into a blot that can only be subjectively read – there is no place for Reason in that, much like how Rorschach’s mask constantly, inexplicably shifts in its blend of white and black, an unsteadiness more becoming of a Ditko villain, especially the new ones we’ve seen here.

Granted, Rorschach is right about a lot of things going on in

Watchmen, and he’s eventually dignified with a climactic glittering death, wiped from existence by Dr. Manhattan, the analogue to Captain Atom, Ditko’s very first superhero – the metaphor needs no major unpacking. Ditko, who contributed greatly to four of six primary

Watchmen characters, would sink into the background as the superhero concepts he worked on adopted lives reactive to their societal context – ongoing adventures, which do tend to supplicate the Individual before the Collective that is continuity. How then, could a compassionate fellow like Moore not feel a little for Ditko? How could a now-decried iconoclast not admire that stick-to-your-guns steel that Ditko has lived, and that Rorschach/the Question/Mr. A embodies?

Yet even at the end there is some sly satire. Rorschach tears off his mask before Dr. Manhattan, revealing his tortured, teary-eyed face, aghast at the compromises all of these Ditko characters have bought into. His face is a Ditko face, but it’s the face generally reserved for the initiators of Force and Fraud, the twisted, neurotic face of the guilty. To put it on a Ditko hero is to show how upside-down the ‘real’ world can be.

Now we’re back at the new stuff. There’s a guilty face, and Mr. A. Technically, the superhero is wearing a white metal mask, but even by the end of the ’60s Ditko had stopped drawing it so much as headgear and just made it Mr. A’s face – now that masks readily collapse into Ditko faces, Mr. A seems more fitting than ever. His beatific gaze is shining with nary a line to cross it, and it’s a look that denotes serenity in all of these new comics, worn by men and women who’ve discovered the way of Rationality.

We don’t need him anymore, really. There are many like him here. We can

be him.

Many new concepts are introduced in the new Ditko comics. I’ve already detailed a few stories and posted a bunch of images, so I’ll be briefer – plus, from examining Ditko’s body of work, I’ve discovered that he’s anti-spoilers. In addition to littering and graffiti, and the United Nations.

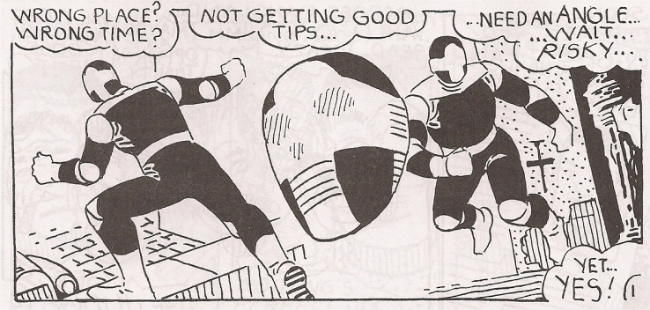

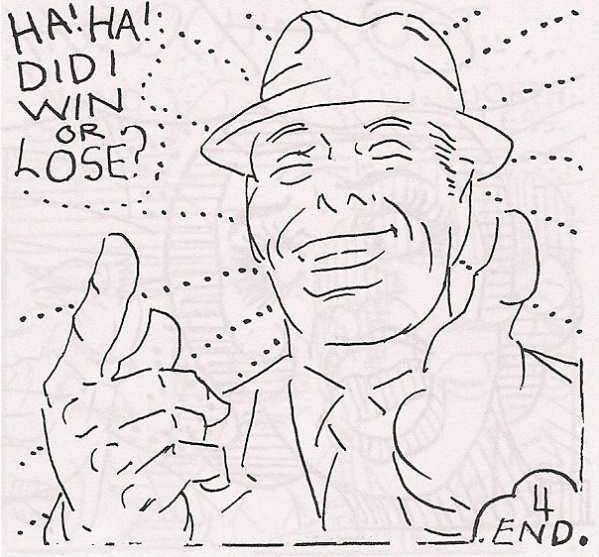

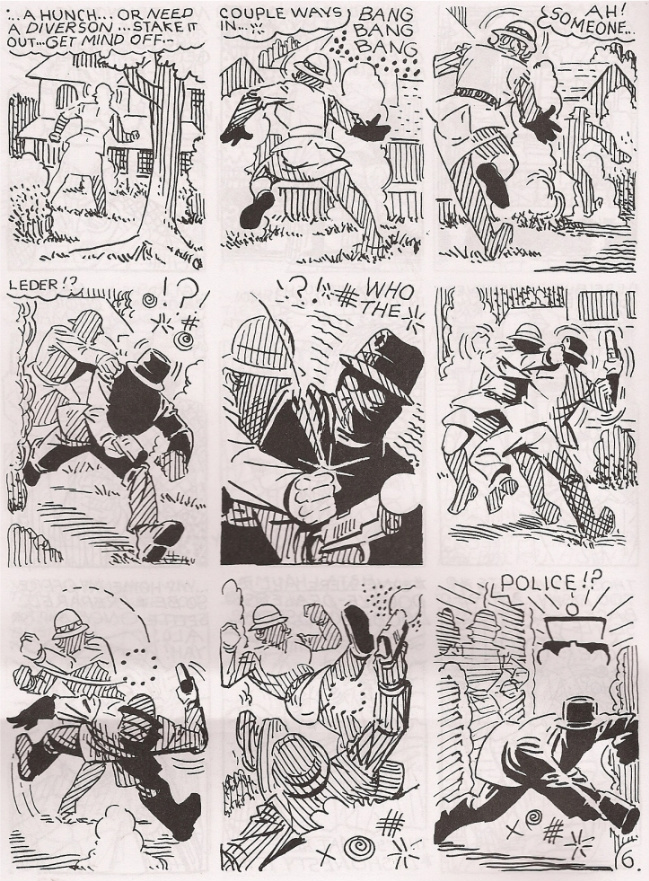

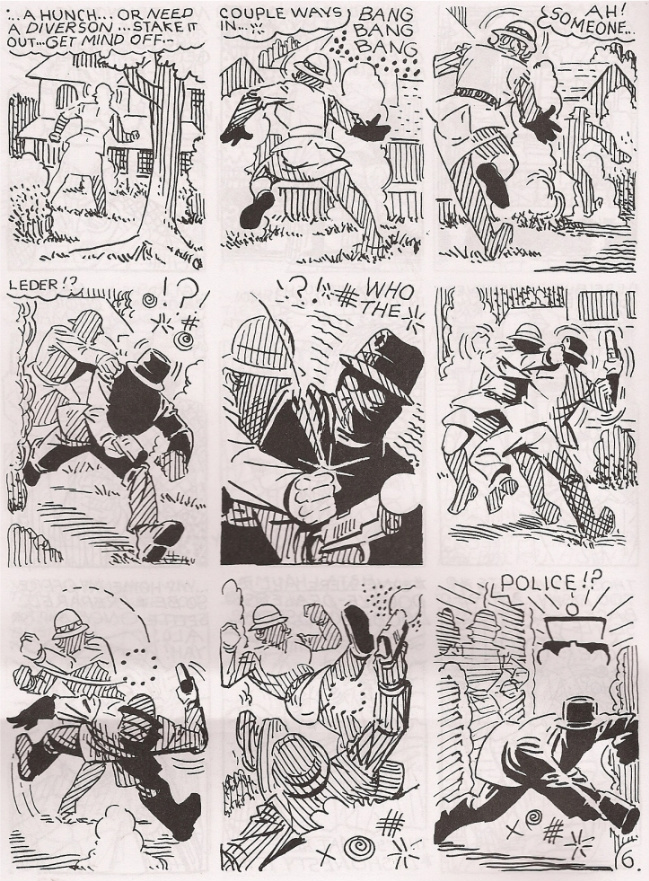

This is “The !?” – a fittingly unpronounceable black and white hero concept centered around upsetting the fake society of crime. Put simply, he dives into gang warfare, kicks a few asses, relieves everyone of their ill-gotten goods, and leaves them sputtering over who the hell is responsible…!?

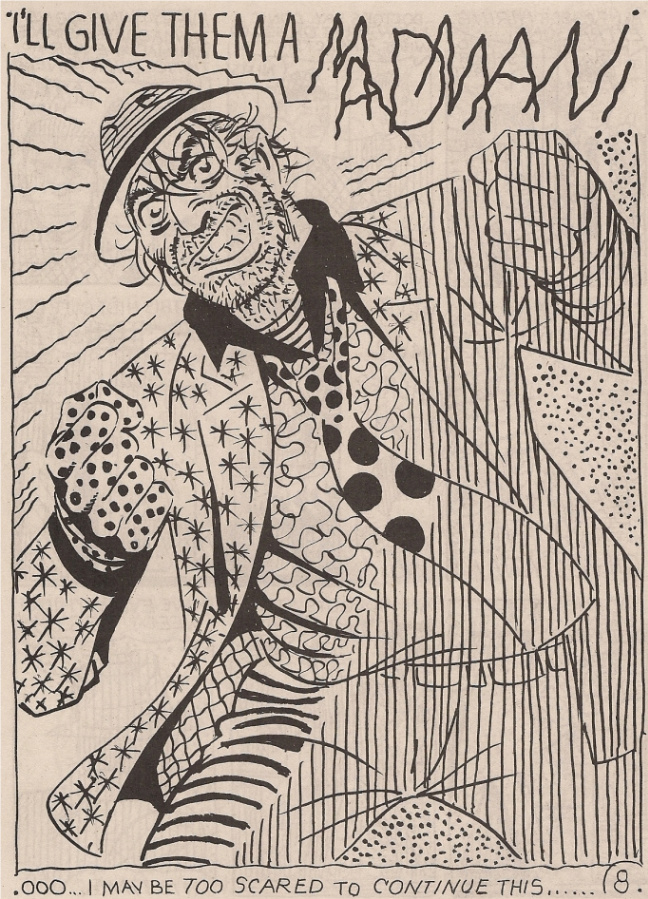

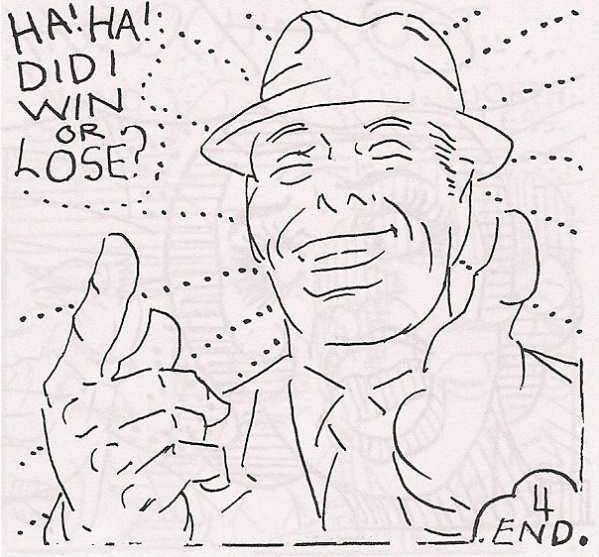

If this doesn’t sound like a great idea for a rich and varied continuing series, bear in mind that Ditko isn’t always interested in continuance. His prized form of superhero comics is short and simple, with the good guys winning – it’s like pre-Code, pre-WWII superhero comics, anthology format and possibly lethal violence and all. Interestingly, several of the continuing characters in the second, present wave of the new comics — the ‘staged’ comics — are given specific settings in different fictional cities of the 1930s. This gives Ditko license to draw as many hats and jackets as he wants to, yes, but it also hearkens back to the historical birthplace of comic books, the place Ditko knew first-hand – like here toward the end of the artist’s road there’s another chance to get it right.

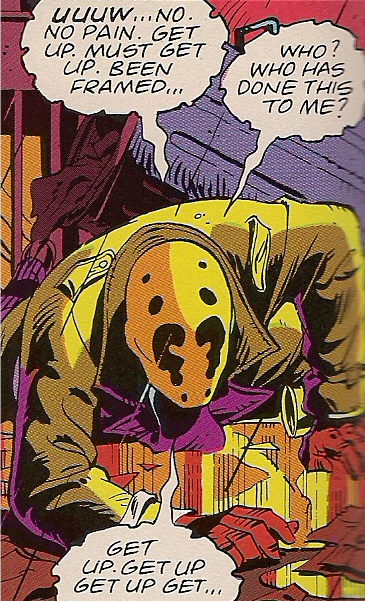

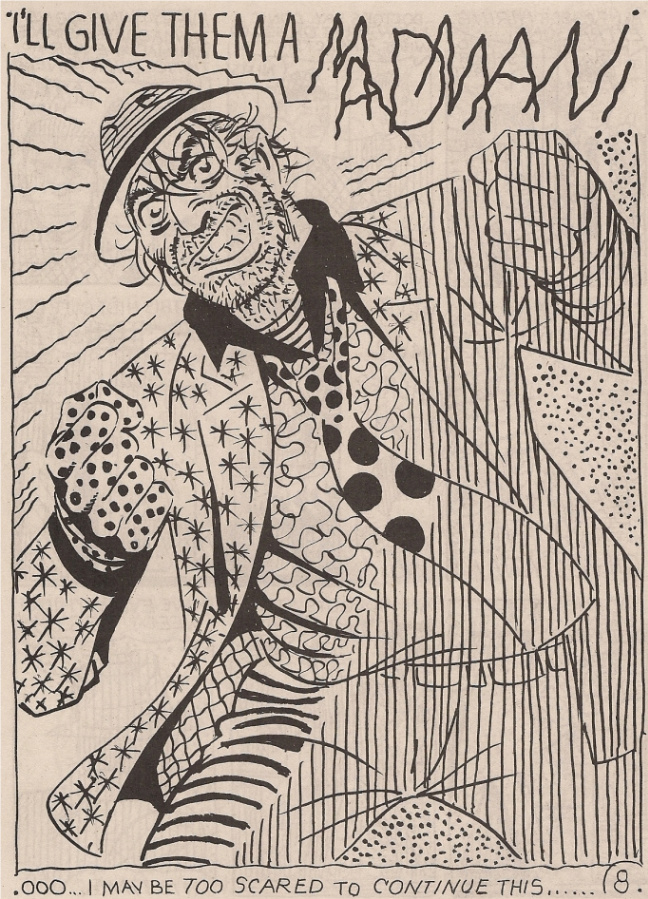

This is the Madman. He lives in the city of Zane, while the !? lives in the city of Emic. Maybe they’ll meet one day, although it won’t be on good terms; Ditko isn’t into anti-heroes, so the Madman is a villain character, a career freelance criminal, Matt Madder, who was framed and put away and went crazy on drugs, and now he’s escaped to terrorize basically everyone. His mental state is indicated by his dress sense — not quite evil lines waving and crossing, but various Ditko line values co-existing incoherently — but his real effect is on society. Zane is not among the more Rational municipalities of the Avenging World, and the Madman’s stories therefore focus on how much he disrupts the rapacious lives of the guilty.

This is the Outline, who’s second only to the Hero in most appearances in the new comics. He’s the Venom to Mr. A’s Spider-Man, looking superficially like his good counterpart but functioning as more of a cruel, impulsive force. He can pass through anything, and cannot be seen. Usually he creeps up to people and coaxes out their inner greed, usually leading them into disaster, or even the specific clutches of the Hero, in a titanic team-up. Sometimes, though, people repent, and sometimes unexpected consequences crop up – it makes little difference to the Outline, creature of Ditko’s ‘outline’ style, a spin-off of heroism itself into more of a cosmic actor, entirely detached from corporeality. All of the endings are going to be the same, right?

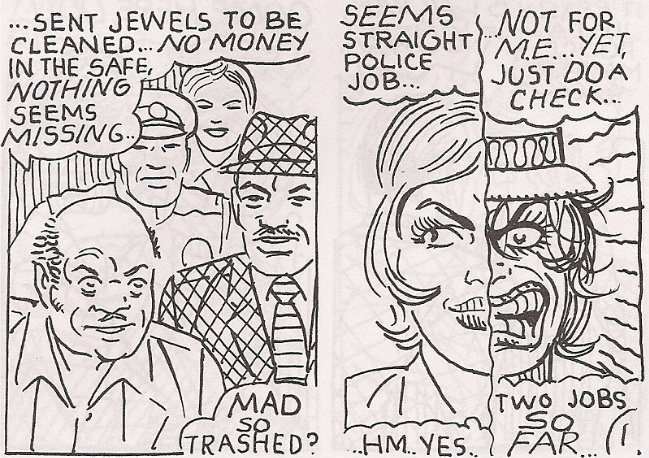

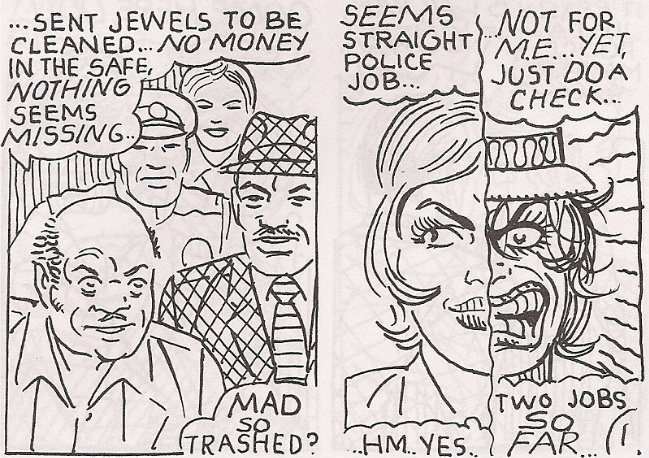

Miss Eerie, Ditko’s most interesting new creation, lives in the city of Mizzen. Her real name is May Ero, and her father and brother are police officers, though she is a private investigator armed with a terrifying mask for special investigations, because women can’t be cops. This is a rare occurrence of Ditko attributing irrational characteristics to the police, in that sexism ignores the facts of the individual in favor of generalizations. Racism too – fascinatingly, while a few supporting heroic characters are racially black, these 320 pages of Ditko’s black and white world contain no non-white villains. Is Ditko-the-fan keenly away of the history of ugly caricature in comic books?

Anyway, Miss Eerie appears in

Ditko Presents and

A Ditko Act 3, although her best story is in the new-new

Act 6. A string of robberies of shady types has broken out, and nobody has a clue. Meanwhile, May runs into a guy she used to know. You can tell where this is going.

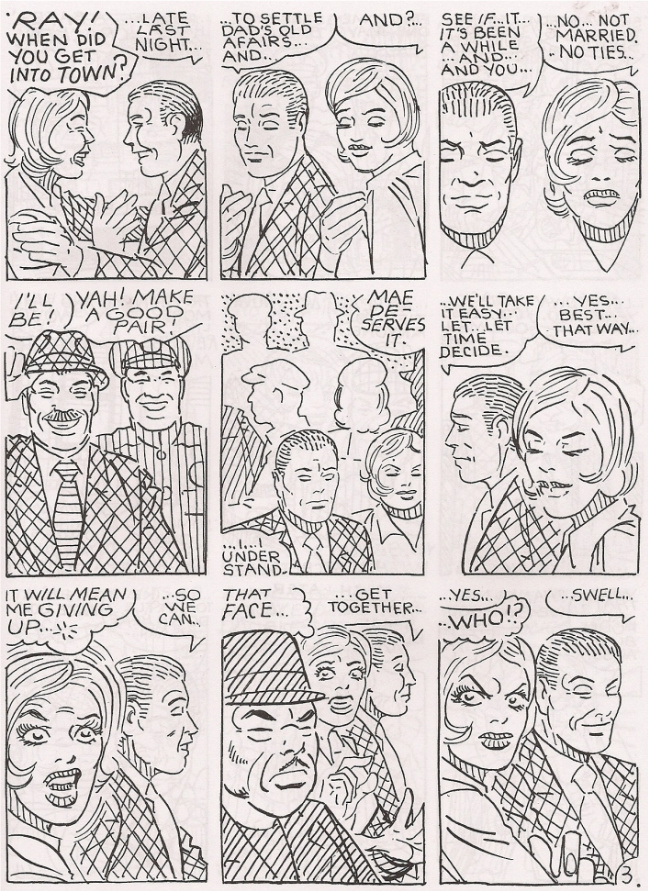

I love this page so much; it’s my favorite thing Ditko has drawn in years. The flush cheeks in panel 1 give way to a 180 degree pivot in panel 2, both characters posing identically like demure icons, then facing front in panel 3 in nervous, regretful, isolated regard, mirrored in panel 4 by the overjoyed onlookers. They grow happier is we draw closer in panels 5 and 6, until the flopped perspective in panel 7 marks May’s snapping back into Hero mode and pondering the case for the rest of the page. The writing pays off well here, with Ditko’s clipped words touching on something elusive and sad, only to see both character’s trains of thought/talk diverge sharply in the bottom tier.

Before long, Miss Eerie has sprung into action, even as May ponders whether to give up the Hero game for some domestic arrangement. There is no particular iconographic significance to this page, just two characters struggling and lunging and diving in and out of shadows, rather nicely rendered, given that most everything is filled in with only rows of lines. It is confusing to the characters, but not the reader.

Of course, May’s potential lover is the masked man, who’s been ripping off the men who cheated his father, a silent partner in their scams, a classic gray actor among black villains. The philosophical considerations are delicate here, for the tragic Ditko reader, because it could be argued that the son is only acting with “retaliatory force” – wait, no, Ditko makes sure that the ripped-off man insists he’s clean now. Reform is possible, there was a cooling period. Then, is he like the !?, swiping criminals’ property as a means of attacking their community? Ah, but Ditko throws in a shooting, elusively indicated without much detail. To take life would require beating back a mighty Force, and the boy was the initiator there. A judge, Ditko, might have to consider his ruling, but Miss Eerie is instantaneous.

You could say she’s defeating herself. How can she be happy like this? How is this any way to live?

She could look to Mr. A, who in a 1969 story,

The Community U.N., faced a nearly comprehensive rebuke for his actions. You can’t say Ditko lacks in self-awareness. Retained by leading citizens to study the problem of crime in the city, Rex Graine elects to dig deep into legitimate men with connections to criminal figures. The citizens are aghast, but Graine knows that A is A, and legitimacy cannot mask corruption. He is publicly and privately accosted, and causes citywide outrage at the brutal beating he hands an attacking thug. Like in a proper Chick tract, all of the real-world criticisms lodged against the work are incorporated into it as insults slung at the hero, who brushes it off as the chattering of bugs, because he can guess the ending. His own newspaper denounces him. He has no visible friends, and certainly no wife or lover. It doesn’t matter. He is called evil and inhuman. It doesn’t matter. The story doesn’t even tell us about his recovery in social status; maybe it doesn’t happen.

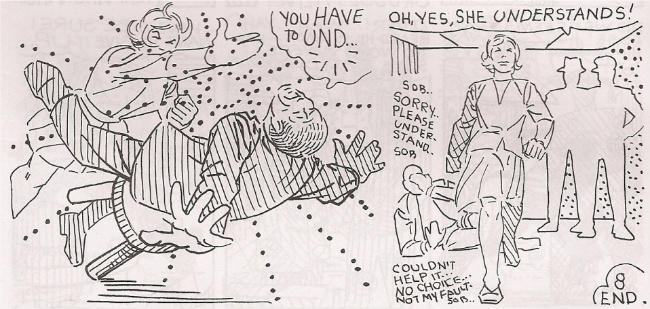

But the ‘realistic’ scenery of Ditko’s story does fade away on the last page, leaving Mr. A and an especially nervous citizen teetering on opposite sides of the white and black card, one of them bound to fall. And what do you fall into, when you’re not at your best?

***

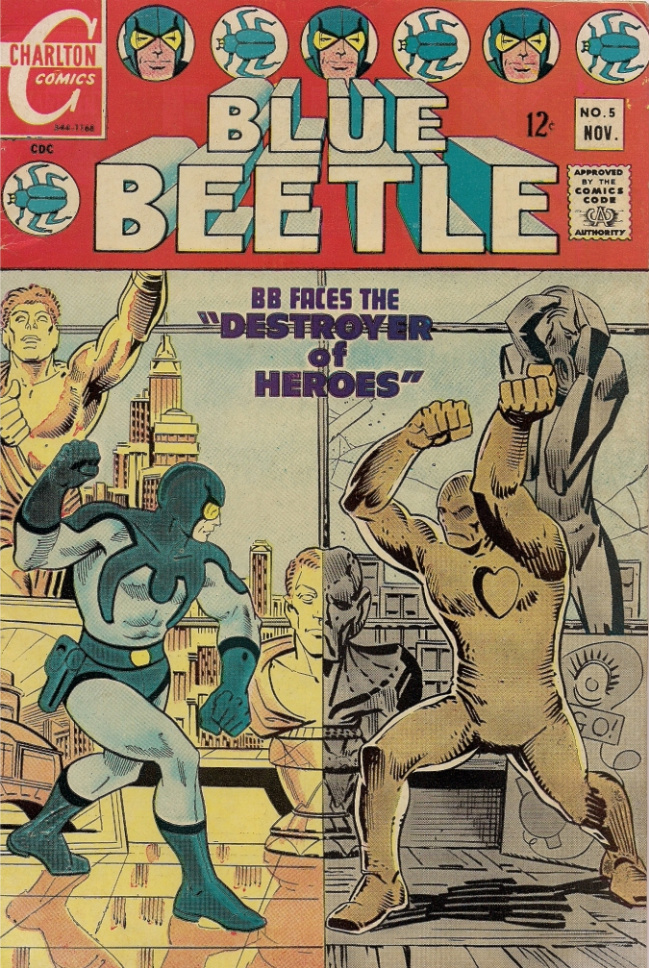

III. A Short Review of Blue Beetle Vol. 1 No. 5, Published by Charlton Comics, Nov. 1968

Blue Beetle #5 is among the quintessential Ditko comics. It was the final issue of Ditko’s revival of the series, starring his creation, Ted Kord, and the last time Ditko would have some semblance of control over the series’ characters and their presentation; a one-off comic,

Mysterious Suspense #1, had appeared the prior month, patched together from completed back-up strips starring the Question and material planned for an ongoing series of his own. Ditko had already completed an additional Beetle story too, which wouldn’t be seen until 1974 via the

Charlton Portfolio, a special issue of the fanzine

CPL (Contemporary Pictorial Literature), contributors to which included Bob Layton, Roger Stern and John Byrne, all of whom became professionally associated with Charlton. Again: fans, pros, zines.

In contrast, 1968 was an ‘in between’ year for Ditko’s artistic development, coming the year after Mr. A debuted in

witzend, and the year before he began to author the first incarnation of

The Avenging World in that same forum. Yet the cover of

Blue Beetle #5 is a classic Ditko split image, profoundly familiar to readers of his fanzine/underground/self-published works, setting opposing forces against one another. Kord’s side of the conflict is golden with towering spires behind clean glass, representational art and the finely-detailed human figure. Against him is all the negative signals we’ve seen in Ditko’s recent work – the color gray, jagged edges, spindly lines. Careful excerpting of the man’s panels notwithstanding, it does appear that non-representational (‘abstract’) art is firmly on the black end of the card, properly tossed to the floor on the bottom right rather than cluttering some perfectly good wall with its bullshit.

There’s more though. Temporally, this is a very specific comic, and something of a self-contained crossover issue, in which Vic Sage participates as a character in the main story, a subplot from which continues and resolves itself in the Question’s backup feature. Ditko is only credited with the art in the Beetle story, with the script attributed to D.C. Glanzman, but it was typical of Ditko at that time to ask a dialogue credit be given to Glanzman on Question stories Ditko had actually written entirely on his own; from my reading of Ditko’s work, it seems likely that he also wrote the Beetle story in this issue, with Glanzman’s participation probably limited to polishing the dialogue without changing the meaning, all of which is extremely specific to Ditko.

As such, above, three visions of Ditkovian heroism share a panel, and it’s impossible not to notice that by this time in the book’s progress Ditko had taken to drawing Ted Kord

exactly like Peter Parker as of his final issues at Marvel. Blake Bell, in his 2008 book

Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko, suggests that Vic Sage’s orange hair is modeled in homage to Howard Roark of

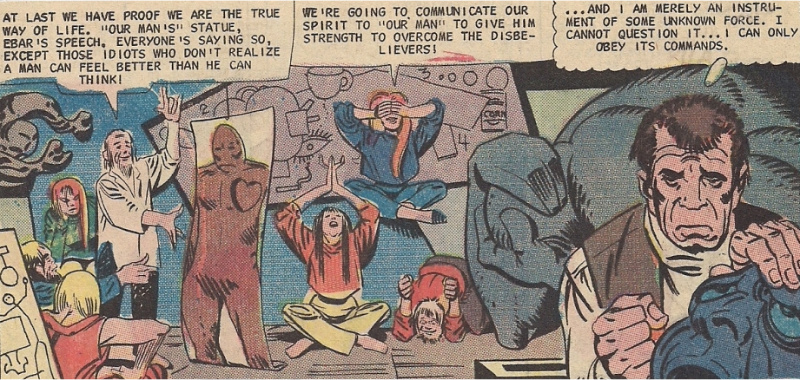

The Fountainhead, with sneering anti-heroic collectivist art critic Boris Ebar — to the left of panel one — an Ellsworth Toohey stand-in. Neither are the lead character in the Beetle’s segment of the issue, but can be taken as representatives of Rand-derived poles marking the two regions of the Avenging World, ‘background’ characters as the backdrop to Kord’s/Parker’s struggle… against…

Well, the Beetle’s opponent is called Our Man, which is not so far from

Iron Man, a Marvel superhero initially visualized by Jack Kirby as a lumpen mass of armored humanity, until Ditko redesigned his costume into the angular, more heroic form still familiar today. Note the absent heart on his chest, symbolic of all the frustration and futility that is the sum total of human life per Mr. Ebar, and thus preferable as genuine art to classist, pretentious, condescending representational kitsch; it’s not so far away from hearing cartoonists of a certain post-Ditko generation chafe at the dismissive attitudes of their abstract expressionism-addled art teachers toward cartooning, except Ditko isn’t interested in simple aesthetic conflict. The absent heart can also mark the injury to one Tony Stark’s physical heart, an infirmity Ditko apparently sees as weakening to the heroic concept – as Our Man charges around Hub City, smashing heroic-looking statues to the sneers ‘n cheers of idiotic, unwashed counterculture denizens (primitives) of the type to devour Marvel comics and speculate as to whether the guy drawing Dr. Strange is on drugs or not, two children debate the makeup of heroism:

“You’ll be a super hero with no legs but I’ll give you super powers so you won’t need them and everyone will feel sorry for you!”

“That’s stupid! Why wreck me if you can give me powers?”

Our Man, it should be said, isn’t actually a statue come to life – it’s a depressive sad sack artist (creator of

awesomely tortured sculpture like that to the bottom right) cosplaying as the original work, on a mission to obliterate the phony, archaic illusion of heroism in art. He is probably my all-time favorite Steve Ditko character,

spouting a parodically non-stop self-pitying internal monologue — in the Mighty Marvel Manner, mayhap — all while clad in a borrowed outfit derived from Marvel’s preeminent superheroic stylist. The Blue Beetle, in contrast, is a revamp of a superhero property dating back to 1939, but underneath his costume he is obviously, visually, Peter Parker, here as intended by his originating artist, no longer a simpering nerd but a steadfast genius scientist and witty righter of wrongs. The sad sack, then, is but a replacement, a fanboy-gone-pro inhabiting an ugly work to make it uglier, while Ditko’s hero is consistent beneath the costume and heroically transformative.

The story is somewhat reminiscent of one of Kirby’s own works, issues #5-6 of his

2001: A Space Odyssey, as much an individual transformation of a preexisting work as Ditko’s Blue Beetle, and doubly so a cry of agony against the superhero comics scene, depicting a dissatisfied superhero fan of 2040 getting off his ass and discovering a world of real conflict, ending with his growing out of such genre trappings and evolving into something else. Ditko likewise isn’t pleased with superheroes in his story, but unlike Kirby his idea of evolution isn’t transcending any damn thing but purifying the nature of superheroism, driving out the stain to leave only pure, just white. This is an unpopular move, he knows, and so rocks and bullets are launched at Kord from the public, just as the public hated Spider-Man, and just, it must be said, how Ditko depicts fandom as opposed to him in his recent comics. He is Ted Kord, Peter Parker, Vic Sage, Mr. A – it’s all him.

And you may ask yourself, “wait a second, Ditko doesn’t legally own Spider-Man or the Blue Beetle or the Question, so isn’t their owning entities, Marvel and DC, merely exercising their individual discretion on how to make use of their property?”

The Avenging World, the 240-page as-of-now final edition, sets forth the artist’s philosophies at considerable length, if not always with great clarity; nonetheless, it is almost certain to be Ditko’s most detailed personal guide to what his art is ‘about,’ collecting comics and essays from across three decades. The detail above is from

Laszlo’s Hammer, a revision of a comics-format essay from 1992; an entirely separate essay can be written on its various narrative devices and symbols, but critical to our current purpose is the titular motif of a man approaching a masterpiece statue with a hammer and attempting to destroy it, the same premise as in

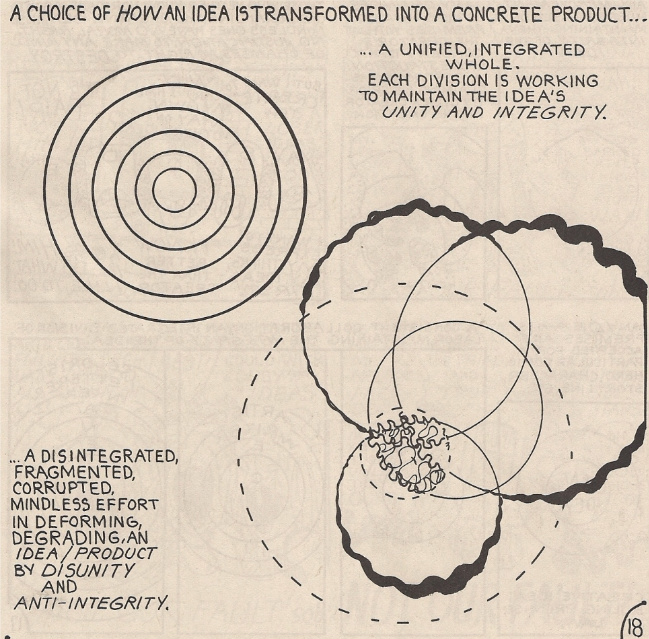

Blue Beetle #5, but expanded into a metaphor for unprincipled artistic creation, encompassing both specific acts of creation and outside meddling in ‘collaboration’ with a creator.

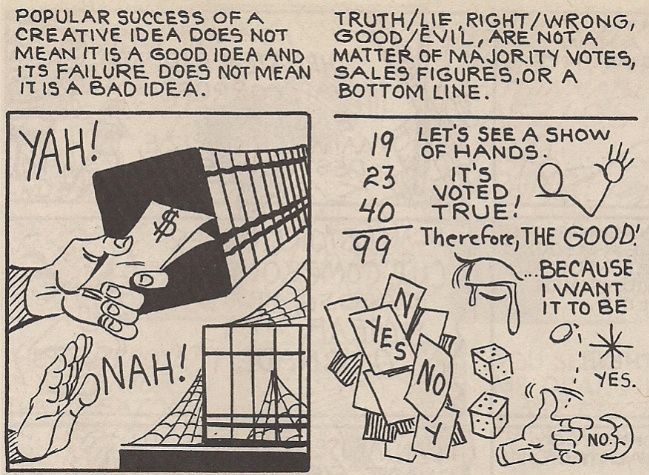

It looks very familiar, broken down into visual elements. The “unified, integrated whole” is perfectly smooth, separated (individual) lines forming a bullseye, not unlike the logo Charlton began using in the early ’70s. The “disintegrated, fragmented, corrupted, mindless effort is a manic jumble of lines with a ‘core’ (as it is) of Ditko’s gray matter. Inherent then, to the gray, so prominent in the artist’s newest comics, is the black soul of compromise, of objective wrongs; the chaos of the Villain is Marvel challenging Ditko’s ideas, of breaking the toys. You have to understand, in this concept of art, of

life, there are objective underlying values, and art that does not serve those rational values — “to portray man, his human potential, at its highest level, of man the hero, a man of justice, to self-create all that he can possibly be – in a non-contradictory manner,” is, in the words of the rational actor, Vic Sage, “trash to me.”

Randians are often portrayed as eternally, politically in the thrall of capitalism. This makes Ditko easy to dismiss by association, because his own ideology has distanced from everyone who’d make him money. Why, the old fool is isolated by his own hand from any business success, a fighter for unrestricted business whose rigid politics have ensured his own economic marginalization. It’s not illogical to laugh at a joke, and so we can laugh at Ditko, or perhaps bemusedly wriggle our chins at the irony and curiosity which we gaze upon from well above. Or, from a safe distance, we nod at how impossibly badass he is for turning all the monied scumfucks away.

Consistently, this is not a truth reflected in his work or his life. Populism, frankly, is a species of collectivism, and the values Ditko cherishes stand plainly apart from economic success. It goes deeper. Elsewhere in

The Avenging World is an adventure comic from 1973,

A View of Justice! It was reprinted previously in Fantagraphics’

The Ditko Collection vol. 1, at which time editor Robin Snyder deemed it “a powerful, moving story with a sentimental and uplifting ending which would have had me on my feet and cheering if it were on the screen.”

It is, by my estimate, the most ideologically extreme thing Ditko has ever made, depicting a heroic doctor brought off a tourist bus in a vaguely South American setting to tend to a Communist leader shot down while fighting fascist occupying forces. The doctor is not a resident of South Park and therefore the truth does not, in fact, lay in the middle; instead, he rejects both as forms of Force and idealistically refuses to operate on the wounded man. A horde of unsuspecting bystanders are gunned down as a result, which is terrible, but the Hero castigates his agitated fellow tourists for spouting meaningless irrational contradictions and delivers a rousing seven-panel speech on the practice of Justice.

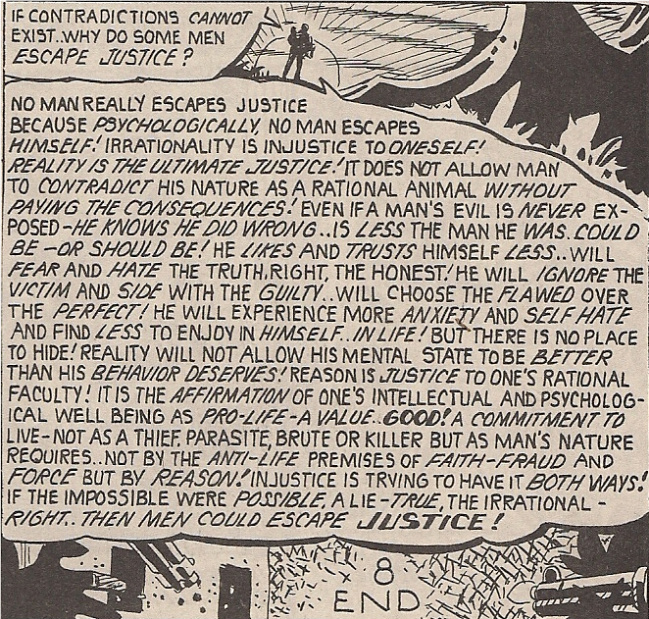

In the foreground, a delicate nurse is so moved by the Hero’s words that he eventually turns action hero and guns down a whole room of Villains. As the tourists flee, the Hero stays to operate on the wounded nurse and manfully disarms a filthy Statist. “We became brothers – brothers of values!” the Hero exclaims, carrying the wounded man in his arms. The remaining tourists are shot to death in the crossfire between opposing sides as the Heroic men stride into the rising sun. A question arises, and is answered:

Half a decade before that, the Question walked out of

Mysterious Suspense #1, and indeed any semblance of control Ditko would ever have over him again. It is the most famous sequence Ditko has ever put together on his own, and the culmination of all his Question stories, which typically ended with the Hero affecting absolutely no substantive change on society. It doesn’t matter, as the Hero strides forth, and his broiling opponent

straight-up loses his shit as the viewpoint pans down to catch his iconic clenched hands; my mother used to say it’s not okay if nobody knows you did a bad thing, because God knows. If every Individual in Ditko’s world is their own God, then, yes, they know. God knows.

One month later, in the backup story of

Blue Beetle #5, which you’ll recall was completed before the

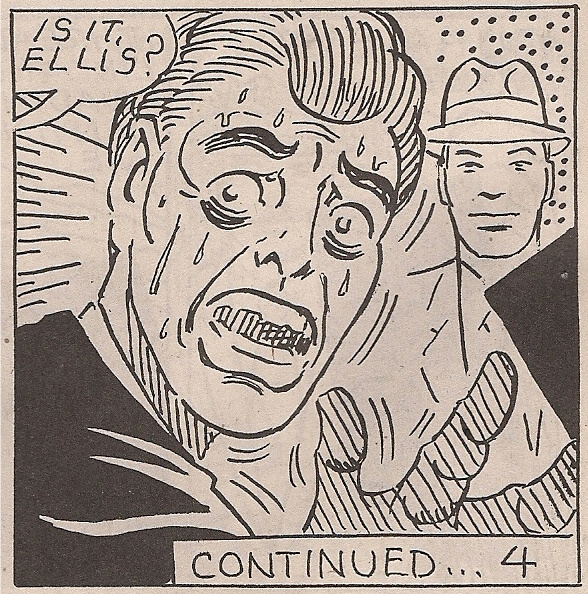

Mysterious Suspense material, the scene shifts from the conflict between Ted Kord and Our Man — overexcited hippies/superhero fandom seized bits of the sad sack artist’s costume and built a shrine to it while the man himself simply gave up on supervillainy in a fit of depressive fatalism — to the Randian stand-ins of Vic Sage and Boris Ebar. The latter is trying to pass around a hilariously downcast painting of stomping feet and a man burying his mouth in his hand next to a giant empty tin can and a cigarette butt, only to become upset at a painting Sage gave his co-worker Nora, showing a grinning he-man standing with hammer and chisel atop a mighty structure.

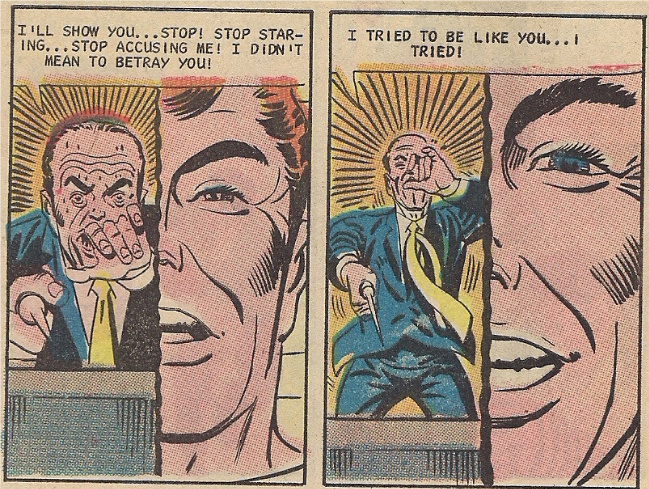

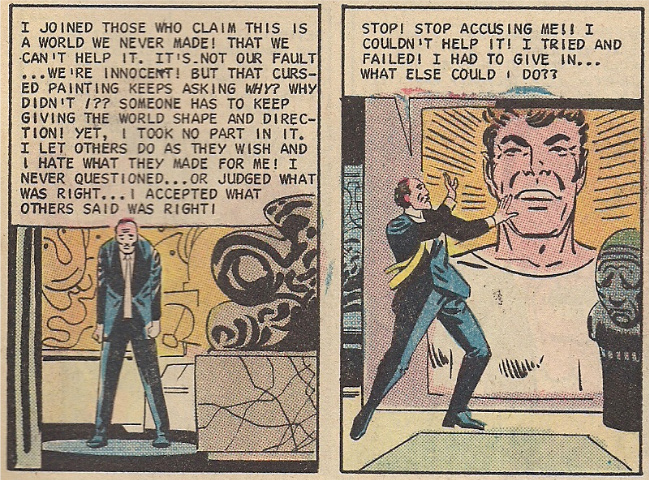

We soon discover the critic’s denunciation of the art as “childish” and “an insult to man and humanity” carries a personal charge rooted in his youthful failures; his disgust with the notion of Heroism drives him to send thugs — all critics have them, I’ve got, like, twelve — to wrest the picture from Nora and destroy it, obliterating property for the sake of a mystic salve. Needless to say, the Question foils this scheme and proceeds to extract a confessional monologue from the critic by gassing his apartment so as to cause the hated image to arise, a j’accuse.

Ditko does not strike me as a religious man — and has, in fact, depicted evil men wearing black clothes marked “FAITH’S GOOD” holding up crosses while kicking good men into the open mouth of a giant skull — so this is Hell in the Avenging World. An endless torment of frustrated ambitions, the angst of compromise, dichotomously portrayed on panel as smooth, smiling, cool, bright, white Mr. A Hero lines against the sweat and wrinkle of nearly every puny gray human on Ditko’s pages.

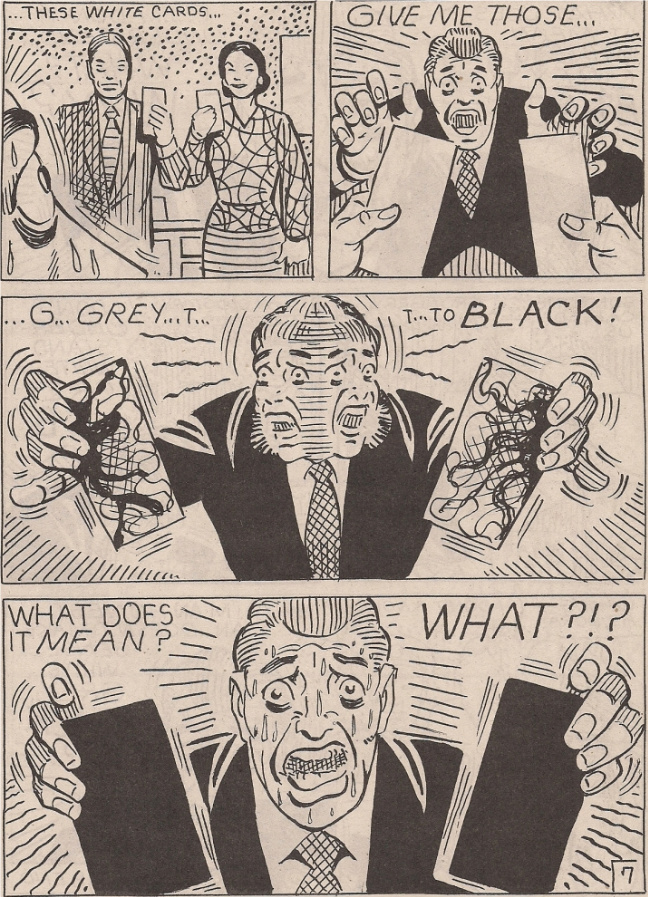

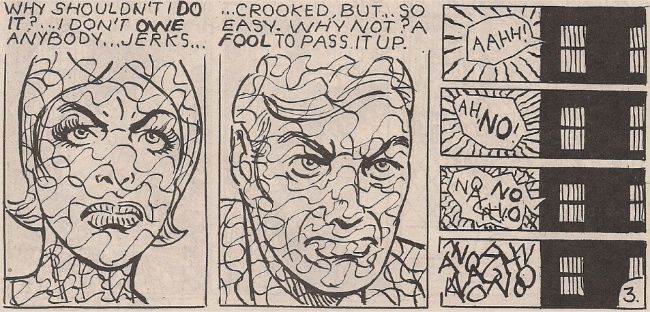

And among the 320 new pages Steve Ditko has created in the last three years, there is a curious two-part story,

The Partners, which appears in

…Ditko Continued… and

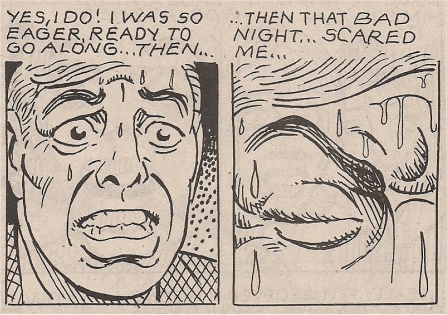

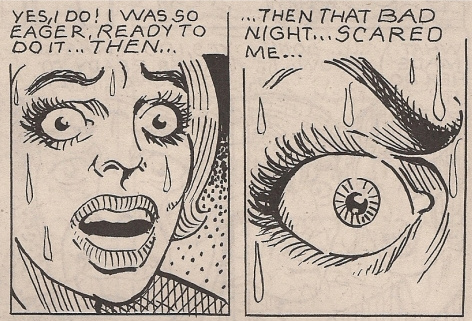

Oh, No! Not Again, Ditko! The first part shows a squiggly-gray woman plotting to steal a million from her office. She suggests her theory to a male coworker, who becomes diseased with gray squiggles himself as they speak. A fall guy is selected, even though she is a nice and helpful worker. Privately, there is individual concern.

A dotted light pierces the shadows as an unidentified culprit, acting alone, is caught.

In the next issue, the final two pages of the story are presented. They are alternate endings, matching one another in terms of layout and nearly identical in terms of dialogue. In one, the woman is apprehended as the culprit, and the man repents.

In the other, the woman is clear of the gray disease, and the man goes down.

There is no difference between men and woman, save for biology. There is no distinction between class. There is no substance to racial divisions in the face of Force/Fraud and Justice. There is no meaning to Western and Eastern culture so that they violate the rights of property and life. There is no logic to religion, and to respect differences between faiths is to respect the anatomy of shadows obscuring Reason. There is no difference between you and me, save that we are Individual.

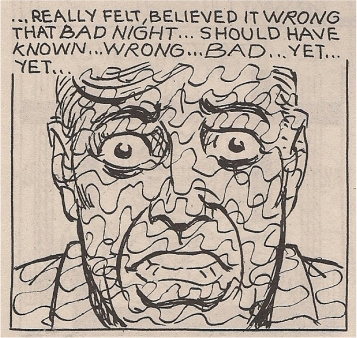

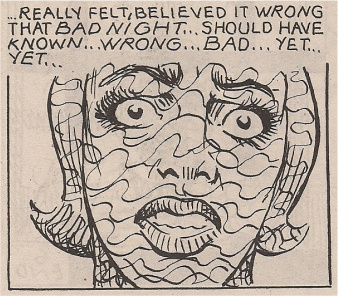

And Individuals are subject to the cutting tension of knowing what is Good and Bad, and Ditko, while prolific with heroes, hones in on as many faces shuddering with torment. Why are you upset all the time? Why are you dissatisfied? Why are you unhappy?

It only looks easy on the page. But Ditko knows this struggle, summarized in every Ditko face. These are no longer only genre comics, these are sketches from the street, dispatches from the front. Ditko is everything on these pages, and so he is

of these pages, hovering above and through them at once, 100% man and 100% God, living as he sees fit, getting by under his shared universe rules, and it’s so hard, it’s so hard, it’s so, so hard, but he is still here. He is still here, he is still here, and where, dear reader, are you?